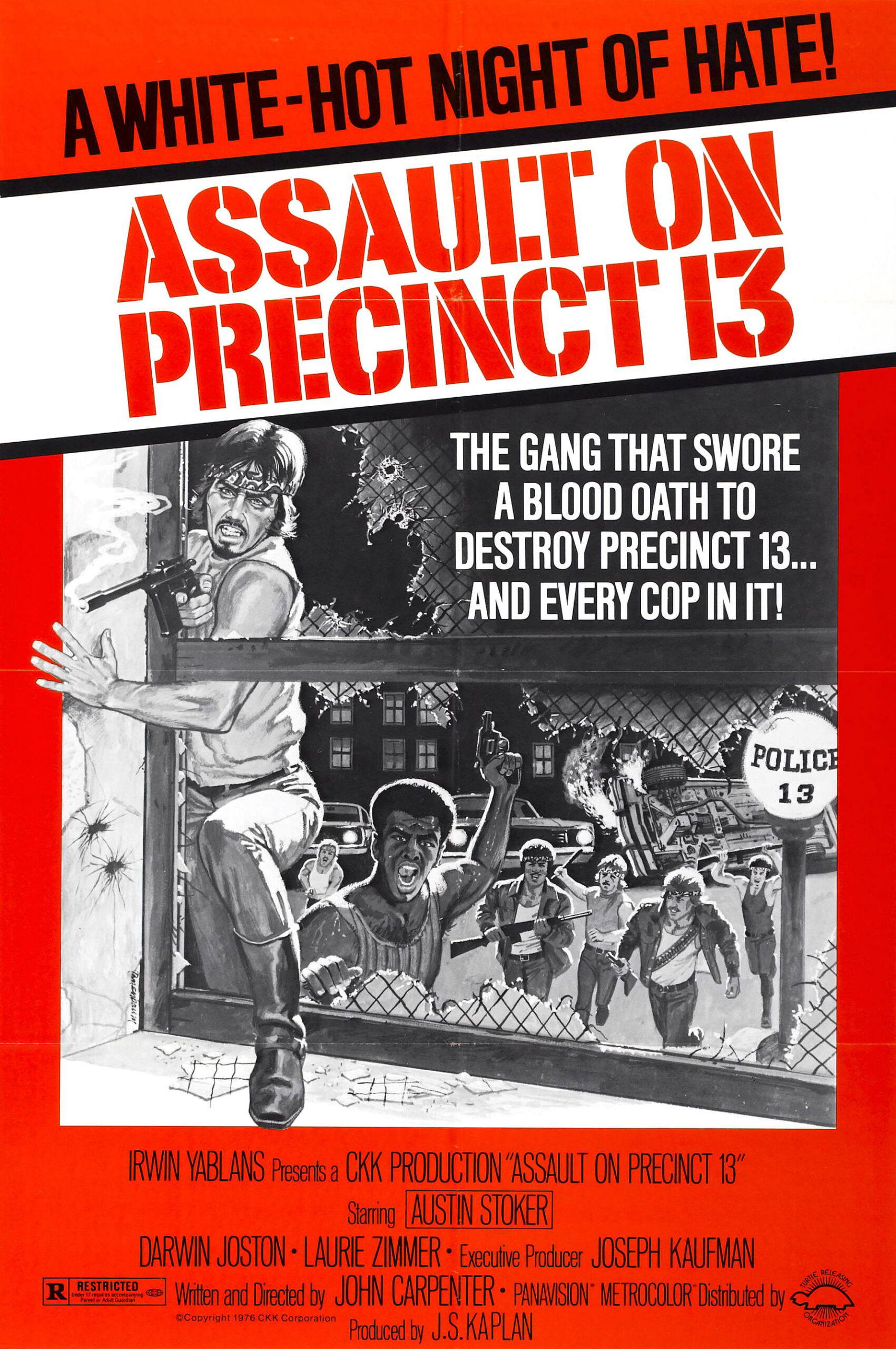

A look back on the most ultimate action movies from the legendary writer, director and composer.

Welcome to our Carpenter watchalong series! Every week we watch one of the director’s action films. Today, we start off with the action thriller Assault on Precinct 13, the film that put Carpenter on his path to making genre film masterpieces.

UAMC Reviews ‘Assault on Precinct 13’

“There are no heroes anymore, Bishop. Just men who follow orders.”

The first thing we hear is a tense synth score in the opening credits, building anticipation to six members of the gang Street Thunder attempting to escape after stealing a stockpile of guns. Carpenter drops the audience straight into the action, erupting into a massacre when the police ambush and shoot down the gang. The gang’s warlords take a blood pact to pledge revenge on Los Angeles itself by targeting and killing random citizens.

Carpenter then takes us to a scene with a man giving his daughter money to get a vanilla twist at an ice cream truck. The electronic score kicks in again, slowly intensifying the sense of apprehension. As a first-time viewer, seeing the girl get shot was shocking due to its sudden and visceral act of violence. It reminded me of a scene in another ‘70s film, The Long Goodbye, where the gangster Marty Augustine suddenly strikes his girlfriend’s face with a glass bottle just to intimidate a detective. Both films use these scenes to depict societal decay in the 1970s and the monsters that it produces.

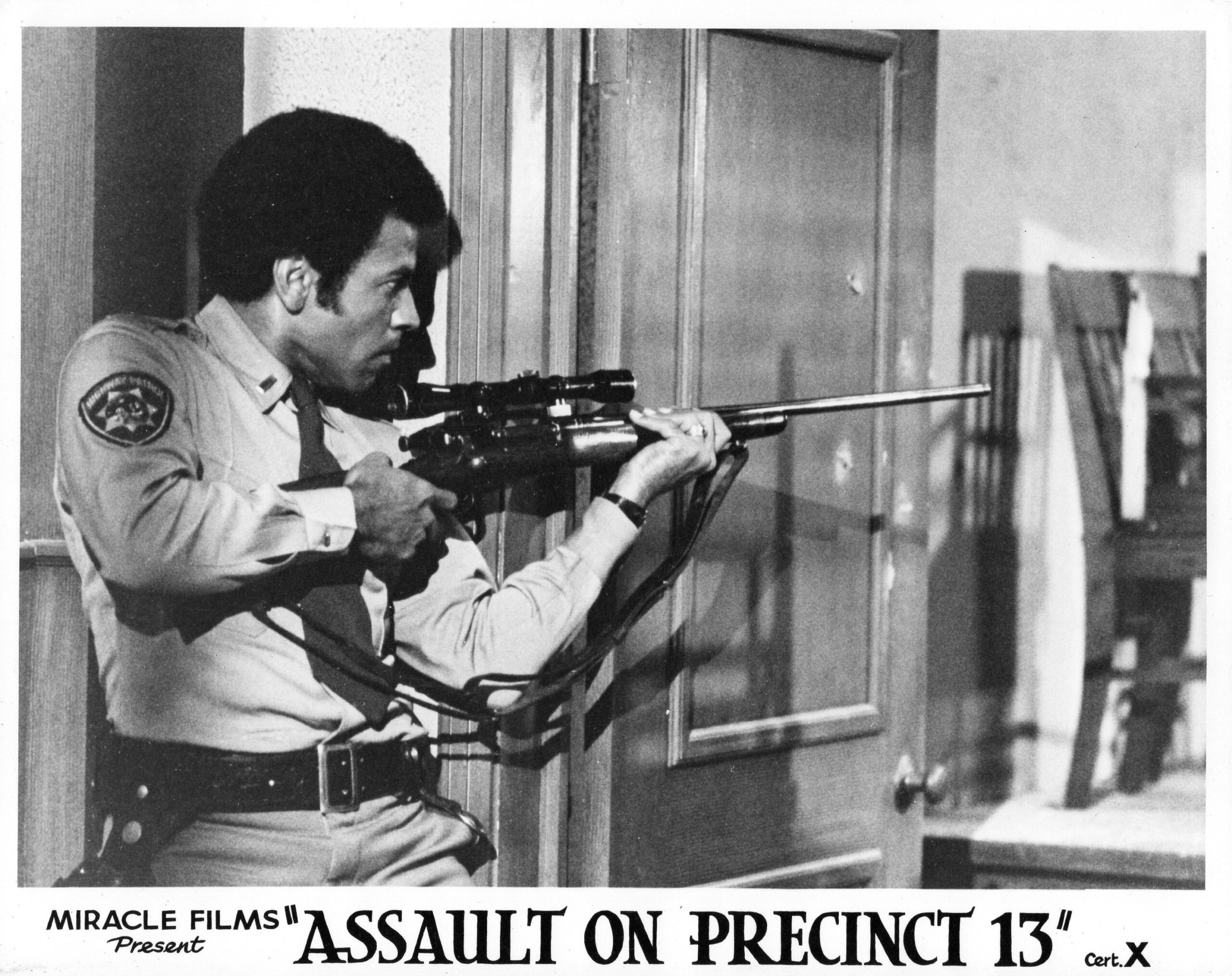

This sequence sets the rest of the movie’s events in motion as the father gets revenge on the shooter, and in retaliation, the gang pursues him until he manages to escape into a closed police station. The only people left to protect him are two police officers, including the newly promoted Lt. Bishop (Austin Stoker), and two office workers. The stakes are raised even higher with the arrival of a prison transport bus containing three prisoners, one of which is Napoleon Wilson (Darwin Joston), a convicted murderer on death row.

Wilson is a character that we often see in films today – an antihero of sorts with equal shares of charm and charisma. He represents a failed justice system. When we first see him in prison, he is kicked out of his chair by the warden for little more than a sarcastic remark. Wilson is also made to be sympathetic through his concern for a sick prisoner on the transport bus. This is all contrasted with a priest once telling him, “you have something to do with death,” marking him as destined to be a murderer on death row.

Ultimate Action Meets Screwball Comedy

For a film as quiet and subdued as this, all of the characters at the station have a natural back and forth reminiscent of a screwball comedy. This is most apparent in the “potatoes” scene where Wilson and another prisoner named Wells decide who will attempt to escape the police station through a manhole. When the characters are forced to work together to defend the station, they bond and grow to respect one another. Take for instance when Wilson asks Bishop for a smoke. He’s used to people looking down on him in disgust and outright rejection, but Bishop shows him human decency in his kind response of “No, sorry.” These bonds are cemented later in the film when Leigh (Laurie Zimmer) gives him his first smoke.

All the action converges at the station, transforming Assault on Precinct 13 into a siege film. Carpenter fuses elements of the western and horror genres to enhance the action and set up the sociopolitical aspects of the film. Many of the action scenes are quiet and restrained, creating an eerie and disconcerting atmosphere. This is especially prevalent in the silencer shots, which are not only necessary for plot purposes but also to depict Street Thunder as a force with the ability to kill indiscriminately. Carpenter draws connections to Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo (1959), a western about a local lawman who must protect prisoners against armed invaders. He revises the plot to fit in with the social dynamics of the 1970s by incorporating criticisms of the police and justice system.

Assault on Precinct 13 is also at its heart a zombie film. Taking inspiration from George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), Carpenter uses the zombie genre to deliver his political criticism. In the beginning of the film, we see Bishop driving to his shift at the precinct, listening to a news report on the previous day’s police ambush. The radio host skews the story and fails to mention the police’s direct involvement in the gang members’ deaths. As Carpenter makes it apparent that many gang members belong to marginalized racial groups, the news report justifies the status quo to LA residents that these communities should continue to be heavily policed. In addition, Carpenter characterizes the gang with excess and absurdity. The gang’s long and drawn-out blood pact scene, militant clothing, and indiscriminate killing can all be interpreted as satire of late-70s right-wing propaganda.

Why John Carpenter’s ‘Ghosts of Mars’ Should Not Be Overlooked

But, How Ultimate is it?

In contrast to the well-developed characters holed up in the police station, the members of Street Thunder are nameless and have no dialogue. They act as a mass and are unmovable, both in motive and action. Through their random killings, the film depicts them as a threat to society, but it’s essential to remember that their need for revenge is in retaliation to the brutal slaughter of their own members by the LA police. By having the police set the precedent for aggression, Carpenter demonstrates empathy for the gang and for anybody who gets pulled into the cycle of revenge and violence.

The movie ends with a ray of hope as Bishop, a police officer, and Wilson, a prisoner, walk out of the wreckage together. There is no one hero in the narrative. It’s rather a group of individuals who decided to band together to protect a father in need. Perhaps Carpenter is saying that the simple expression of human kindness across the divide of people and police is necessary to stop the needless violence.

Coming up next week: We watch Escape from New York, the first action film collaboration between John Carpenter and Kurt Russell.

Later:

- Feb. 4: Big Trouble in Little China (1986)

- Feb. 11: They Live (1988)

- Feb. 18: Escape from L.A. (1996)