A case to not kill off the most beloved action heroes of all time.

“That’s a Smith & Wesson, professor. And you’ve had your six!” – Sean Connery uses his licence to kill on his first performance as James Bond in Dr No, released in 1962.

Not so long ago I went to buy a couple of DVDs at a store I haven’t been to for a long time, and the manager, who knows I’m a James Bond fan and I have in fact bought him a couple of Bond stuff some years ago made me the inevitable question: “What do you think about the latest film?” Inadvertently, he asked me something whose answer makes me get into trouble with many people because if you have been a Bond fan for almost 25 years, the ending of No Time To Die will not leave you indifferent, as many reviewers have pointed out.

When I opened up regarding my opinion, which you will see in the next couple of paragraphs although the headline anticipates where do I stand, my acquaintance went to the point: “What do you think of James Bond dying? I mean, is there one of the novels or any source material where he actually dies?”

There was a long time ago a film titled Casino Royale and it was produced by Charles K Feldman, who had the rights for the original Ian Fleming novel, reason why the Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman duo or their company EON Productions couldn’t adapt it for the big screen until 2006, some years after the rights issues were settled. In that version of Casino Royale, James Bond dies.

As a matter of fact, all of the “James Bond 007” codenamed recruits hired by David Niven’s Sir James Bond are blown to bits in an explosion. Similarly, Niven’s Bond has a daughter he’s barely aware of and begins the story in retirement, pushed for “one last mission” that involves his enemies (one of them a relative of his) spreading a virus throughout the world. Looks a bit familiar, doesn’t it?

David Niven and Jean Paul Belmondo in a scene of the 1967 satirical version of Casino Royale, produced by Charles K Feldman.

The point is… that film was done as a spoof, since Feldman was unable to reach an agreement with EON and, afraid to compete against Sean Connery’s version, took a chance to turn the material into a comedy using names like Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress, Orson Welles, Woody Allen and John Huston, who was one of the many directors of the expensive production. The fact that James Bond could die was part of the joke, and a poetic license Feldman took as a way to show the film wasn’t meant to be taken seriously – emphasised by the very last scene where all the Bonds are dressed as angels playing the harps in heaven, except for Woody Allen’s Jimmy who goes to a place where it’s terribly hot.

There was a much more serious and dramatic take on Bond’s death in a 1985 novel by Jim Hatfield, The Killing Zone. In the penultimate chapter, the secret agent is surprised by one of his enemies and ferociously strangled by him. Although he succeeds in defeating the intruder, 007 falls dead into the arms of his female companion, Lotta Head, and the very last chapter features a naval funeral akin to the one of the film adaptation of You Only Live Twice. So… did they kill Bond in the novels?

Not so fast. The Killing Zone was, essentially, a fan novel. Hatfield, an ex-convict, sent the manuscript to a publisher under the guise that it was sanctioned by Gildrose (now Ian Fleming Publications) and for a reason at least two copies were printed by Charter. But no, the company managing the publication rights of Bond’s creator never green-lit it.

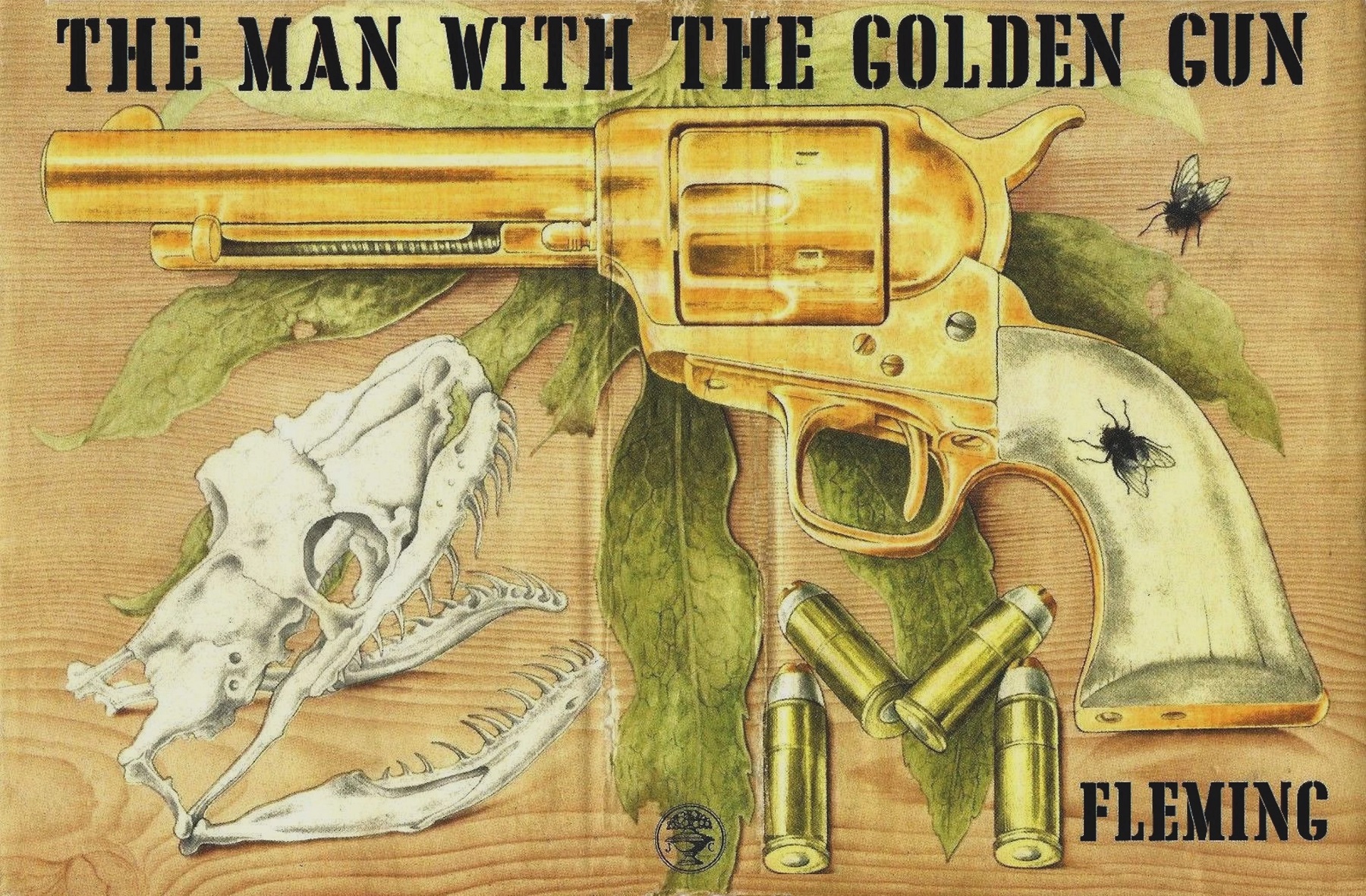

Speaking of the Bond creator, let’s go back to where Barbara Broccoli says she goes back every time she is stuck, as per her legendary father’s instructions: Fleming. Did Ian Fleming kill James Bond in a novel? Does the final Ian Fleming novel, The Man With The Golden Gun, features the ace of the British spies departing this world in some way?

No.

Fleming did toy, however, with the idea of killing Bond off, reason many outlets and writers frequently like to point out the character’s fate was always to die – which, I allow myself to say, it’s wrong. A prime example is one of John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s favourite novels, From Russia, With Love.

Published in 1957, the book that inspired the second film in the EON series begins with a meticulously planned konspiratsia by SMERSH, the executions branch of the Soviet Union, to give a demoralizing blow to the West. Trying to find someone they would regard as some kind of a hero, someone who has foiled all of their operations, the name of James Bond is uttered before the nefarious General G.

And so begins what we saw in the film: the idea of luring 007 to a trap involving a beautiful cryptographer defector and causing his death amidst an international scandal to make the British lose face. SMERSH didn’t count that the girl would have a heart and fall for Bond, but unlike the 1963 film, the book ends with Soviet agent Rosa Klebb poisoning the secret agent with deadly venom and he crashes “headlong to the wine-red floor”.

Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, showing some of the vices he lent to his character.

This is cited by many as the prime example that Ian Fleming killed Bond indeed and had a last-minute change of heart and made him survive in the next novel, Dr No, published less than a year later. To make it more curious, in Il Caso Bond, a 1964 book of essays on the character written by renowned intellectuals like Umberto Eco, it is noted that a newspaper reported that 007 had indeed met his maker at the end of the new Ian Fleming novel and thus thousands of readers complained to Fleming, who explained that Commander Bond was on a recovery phase and ready for new adventures, which they would witness in the book that served as the adaptation for the first EON film.

But even if Fleming hadn’t clarified that the conclusion of From Russia, With Love is, at best, ambiguous. And is closer to a cliff-hanger than a definitive conclusion, like the Cary Joji Fukunaga film and swan-song for the Daniel Craig era is. Bond’s physical reactions to the poisoning are very visceral, but even in that situation he allows himself to make a joke about having met “the loveliest girl” in Tatiana Romanova, moments before his French ally Mathis, who only notices that his friend “looks tired” wants to invite him to “the best dinner in Paris” with “the loveliest girl to go with it”. A far cry from the fatalistic conclusion of No Time To Die, where Craig’s Bond radioed a goodbye to Madeleine Swann and praised their daughter in common, Mathilde.

Let’s move on now to the second “death” of the literary James Bond, which takes place at the end of You Only Live Twice, published in 1964, the same year Fleming passed away as Goldfinger turned Bond into a sixties cinematic phenomenon.

Daniel Craig’s version of James Bond meets the leader of SPECTRE and his foster brother, Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Christoph Waltz), imprisoned in Belmarsh in 2021’s No Time To Die.

Many elements that would make a book Bond fan pleased were adapted in No Time To Die and they would be welcomed if they hadn’t been pitifully taken out of context. One of them is Bond offing Blofeld by strangling him amidst a gruesome swordfight and murmuring the words “Die, Blofeld, Die” while avenging his wife. You probably know this happens in the 2021 film inside a Belmarsh prison interrogation room where the nemesis is fully restrained and this action only causes Bond to act as a pawn of the main antagonist, Rami Malek’s Lyutsifer Safin, who wanted the SPECTRE leader dead for his own reasons.

I describe this because in You Only Live Twice, once Bond strangles Blofeld he sees the villain’s castle is about to blow up and attempts a daring escape by projecting himself over the sea with the aid of a rope tied to a hot air balloon. “Bond let go with hands and feet and plummeted down towards peace, towards the rippling feathers of some childhood dream of softness and escape from pain,” the chapter ended. The next chapter is a full transcription of Commander James Bond’s obituary for The Times, where M catalogues his man as “missing, believed killed” and reports that “hopes of his survival must be abandoned”.

Daniel Craig gives James Bond an explosive send-off in the divisive finale of No Time To Die.

People compare these moments to the “final ascent” of Craig’s Bond, and it’s impossible not to do so because it is very obvious that screenwriters Neal Purvis & Robert Wade (with collaborators that included director Fukunaga, Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Scott Z Burns) were based on these passages. As this Bond is turned to ashes, letting himself die over a rain of missiles because Safin has poisoned with a virus that would kill Madeleine and Mathilde on touch, we move to London and the not-so-affectionately nicknamed “Scooby gang” of M (Ralph Fiennes), Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), Q (Ben Wishaw), Tanner (Rory Kinnear) and introducing Nomi (Lashana Lynch), the 00 agent who was 007 for a long while and gave the number back to Bond because “it’s just a number”.

In a darkened room at Whitehall, they all toast to his memory and Fiennes’ character reads a quote from a book: “The proper function of a man is to live, not to exist. I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time”. This is actually a quote from poet Jack London that Mary Goodnight suggested for Bond’s obituary, as it represented very well the secret agent’s philosophy of life. It is important to note that Fleming only quotes the second sentence and not the first, which has a much more fatalist interpretation. On the contrary, “I shall not waste my days in trying to prolong them. I shall use my time” has an emotional charge that is close to laissez-faire and the way of life of 007’s creator, who died at 56 of a heart attack and health damaged by an excess of alcohol and tobacco. In Fleming’s vision, he wouldn’t mind dying at a relatively young age if that meant enjoying some pleasures he couldn’t live without. But one would hardly imagine Fleming smoking 100 cigarettes and drinking two bottles of gin while making a teary goodbye to his wife Ann and his son Casper. Unfortunately, the interpretation done in the No Time To Die script is much closer to that of killing yourself if you can’t get what you want.

Not everyone believes in God, but by saying “I shall use my time”, Fleming and the literary Bond are already giving a superior being the decision of taking their lives away, in the case of Fleming was at 56, but it could have been at 51 or 63 or perhaps even more – we know of rockstars with not-so-healthy habits who have reached 70. Craig-Bond, in this case, decides that his time has arrived, right there when the cluster missiles fired by the HMS Dragon are about to impact on the villain’s island, a loose adaptation of Blofeld’s “Garden of Death” in You Only Live Twice. He even looks at them as if they were fireworks and the script describes them as “strangely beautiful”. Wasn’t that a bit too much?

Dust jacket for the first edition of Ian Fleming’s final James Bond novel, The Man With The Golden Gun, published by Jonathan Cape in 1965.

So, what is the ending Ian Fleming wrote for James Bond? We have to go to the last chapter of his final novel, The Man With The Golden Gun. Far from the finale of its 1974 film adaptation, where Roger Moore and Britt Ekland sail on the villain’s junk in a slow and romantic boat trip to China, the 1965 book has James Bond convalescing in a hospital after a ferocious shootout on the Jamaican swamps with the title villain, a Cuban hitman under the KGB’s payroll. He is bloodied and battered, with Mary Goodnight by his side. Two things happen here that contradict things we have seen in No Time To Die: the first one is that Bond categorically rejects a knighthood and, while doing so, he also expresses himself against that kind of pretentiousness, adding that he barely used his Commander rank except for a couple of official documents.

In the 2021 film, he unnecessarily remarks to Nomi that “it’s Commander Bond, by the way”. But the most important contradiction with the events of Craig’s final 007 outing is that, while Bond is not in the idyllic state in which he usually ends his assignments in the film series, he is alive and defends his way of life: as Goodnight is assisting him and they share some romantic chat and kisses, James concludes that her love wouldn’t be enough as it would be like “taking a room with a view” and “for James Bond, the same view would always pall”. A celebration of polygamy

There you have it. The literary James Bond didn’t have a proper ending and authors that continued the work of Ian Fleming haven’t terminated him: authors like Kingsley Amis, John Gardner and Raymond Benson took him from the late 1960s to the early 2000s, while Sebastian Faulks, William Boyd and Anthony Horowitz placed him again in period-piece novels set in-between the Fleming novels, which makes the character already impossible to kill unless the upcoming With A Mind To Kill proposes some kind of an alternative continuity. [Horowitz has recently said he wasn’t satisfied with the ending of NTTD and he didn’t kill Bond in the novel.]

But looking beyond the prose of Fleming, we have to look at the context that led to the inception of James Bond and what he came to represent in this world. Fleming wasn’t particularly happy with having to marry at the age of 43 and to calm his nerves he created this exaggerated fictional version of himself (or what he would have liked to be) one day in January 1952 at his Jamaican estate. While it contains great doses of violence and the hero is physically and emotionally hurt at the end, Casino Royale allows the reader to feel the tension of a high-stakes baccarat game in a casino located in the South of France.

The rest of the Fleming novels, while many times much darker in tone than the movies, did allow the reader to experience firsthand the pleasures enjoyed by Bond, be it a beautiful girl –usually in her mid-20s, slightly suntanned and with a deep red lipstick as the only makeup element–, a breakfast made of the finest elements, an expensive cocktail and the lightness of a Sea Island cotton shirt, all in the most exotic places in the world: Jamaica, Turkey, the Bahamas, Switzerland, the Seychelles islands or Japan. “My opuscula do not aim at changing people or making them go out and do something. They are written for warm-blooded heterosexuals in railway trains, airplanes and beds,” he wrote in 1963 adding that he was not “engaged or involved” and had “no message for a suffering humanity”. While others described themselves as authors, he described himself as a writer. While others’ literature was aimed at the readers’ heart, his books “lay somewhere between the solar plexus and, well, the upper thigh” and insisted they were far from the Shakespeare stakes and had no ambition.

Robert McGinnis’ promotional illustration for Thunderball (1965), a good example of what the essence of James Bond is: danger, thrills and seduction.

Not much time before the inception of James Bond, George Orwell wrote 1984, published in 1949. Both writers were British and lived through the depression and shortage caused in their countries by World War II, but while Orwell emphasized the poverty, depression and lack of hope in a dystopian version of Britain and its despotic government; Fleming wrote stories about a British agent who fought a despotic power like the Soviet Union and enjoyed the finest things in life. Much like Winston Smith, the literary Bond suffered horrible tortures at the hands of his enemies and went through really hard times and moments of deep depression, but there was something inside him that made him fight for his life, an instinct of survival that kept him going knowing that his allies and his Nation depended on him. A paragraph from Dr No exemplifies this quite assertively:

“Now he was finished. Now it was the end. Now he would fall flat and slowly fry to death. No! He must drive on, screaming, until his flesh was burned to the bone. The skin must have already gone from the knees. In a moment the balls of his hands would meet the metal. Only the sweat running down his arms could be keeping the pads of stuff damp. Scream, scream, scream. It helps the pain. It tells you you’re alive. Go on! Go on! It can’t be much longer. This isn’t where you’re supposed to die. You are still alive. Don’t give up! You can’t!”

Needless to say, in most novels Bond enjoyed the warriors’ rest after enduring challenging moments throughout his mission and/or he succeeded in foiling the enemy’s plan. In the case of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, he foiled Blofeld’s plan of provoking a bacteriological attack on the United Kingdom. We have that satisfaction even in the tragic ending of the novel where Mrs Bond is brutally shot, and the satisfaction becomes even bigger in You Only Live Twice when Bond terminates Blofeld for good. Although he loses his memory and is believed dead, he shares moments of bliss with Kissy Suzuki that is quite romantic until his past comes back to him and that directs us to the thrilling first chapters of The Man With The Golden Gun.

The big problem with No Time To Die regarding the villain, the tragic ending and the “hope” felt at the end when Madeleine Swann wants to tell her daughter “the story of a man named Bond, James Bond” lies in the fact that Ian Fleming’s secret agent is not only a very loose adaptation of his true self but the fact that he is essentially a secondary character for two-thirds of the story: Malek’s antagonist has no clear purpose, we don’t know if he wants world domination, money or simply revenge.

The point is that his main target is Madeleine Swann. In fact, the whole film seems to be dedicated to her and her hope to get rid of “the masked man” (in reference to the day Safin, wearing a Japanese Noh mask, stalked her in her childhood during a moment that opens the film), which she does to the cost of losing Bond in a poor –and rather insulting– twist to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Why would Louis Armstrong’s “We Have All The Time In The World” be featured as an incidental instrumental in Hans Zimmer’s score or its original 1969 recording during the end credits?

That song, tailored for the ill-fated romance between James Bond and Countess Teresa Di Vicenzo, was reinterpreted for a love story that even the most loyal Daniel Craig era supporters labelled as rushed and depth-lacking.

James Bond (George Lazenby) marries Tracy Di Vicenzo (Diana Rigg) in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the film “We Have All The Time In The World” was written for, with Louis Armstrong lending his voice for the last time in his life.

Much like The Spy Who Loved Me, a novel Fleming himself disliked to the point of adding a contract clause that inhibited EON to use any element of the story except for the title, No Time To Die neglects the legendary 007 to be the saviour of a girl tormented by bad experiences and a lunatic chasing her. Safin doesn’t even have anything against Bond and pushes him to suicide only to destroy Madeleine’s life.

It was already bad for long-time Bond fans to see their hero letting go of this world, but seeing him crawling and bowing to the villain –even when it was a tactic to withdraw his Walther PPK– felt like an unexpected kick in the gut. Bond has never reached this point of humiliation and it was even admired by his enemies and considered someone hard to cross paths with. Take, for example, the film version of Francisco Scaramanga, played by Christopher Lee in the 1974 film The Man With The Golden Gun: the deadliest assassin in the world, the one that “only needed one bullet” to complete his million-dollar contracts, elevated Bond’s reputation to the one of Al Capone. In his funhouse lair, both Al Capone and James Bond had wax statues challenging duelling guests to his island.

And we are talking about Roger Moore’s Bond here, which is usually considered the lightest one in terms of deadliness. In 2002’s Die Another Day, the villain reaches the point of admitting his brief encounter with Bond left him a lasting impression, forcing him not only to change his appearance through a DNA transplant but to base his “disgusting” personality on his enemy’s “unjustifiable swagger” and mannerisms. James Bond is St George to each villain’s dragon. No Time To Die, unfortunately, does exactly the opposite: making it clear that is the villain whose damage will remain even after he’s gone, and no matter what Bond can do, he has succeeded in dooming him.

And never forget, he doesn’t even want to destroy Bond like SPECTRE or SMERSH wanted to do in From Russia With Love (both the 1957 novel and the 1963 film adaptation), he’s doing this to ruin the life of Bond’s companion!

GoldenEye takes a lot of screen time to develop the character of Natalya Simonova (Izabella Scorupco), before she crosses the path of James Bond (Pierce Brosnan).

James Bond is the most important character in every James Bond adventure, no matter how much development you want to give other characters: computer programmer Natalya Simonova in GoldenEye was hugely developed and she never got to diminish his presence, she got her own opponent in the figure of hacker Boris Grishenko, but the big battle lied between Bond and his former friend and colleague Alec Trevelyan, once known as 006. Both The Living Daylights and For Your Eyes Only place 007 and the girl between the crossfire of two old sworn enemies, but as strong or important as these characters are Bond is not undermined at all.

A James Bond adventure, be it a novel or a film, should always represent a tacit chess match between Bond and the villain, as Umberto Eco analyzed in Il Caso Bond. When 007 is left aside and we stop mattering about him, a Bond adventure stops being a Bond adventure. This is evidenced first and foremost in the classic gun barrel sequence in No Time To Die, where right after shooting to the screen the Craig-Bond just fades away and there is no blood dripping down, foreshadowing the film’s finale and driving us straight away to the first encounter between Safin and Madeleine Swann, some two decades before the events of the film.

Created by Maurice Binder in 1962, the gun barrel sequence is the perfect symbol of the secret agent’s strength and invulnerability against every enemy. Anyone could be looking through the barrel: young, old, British, foreigner, man, woman, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that no one can stand a chance against James Bond: soon enough, he will turn, shoot, and the anonymous enemy will bleed. Bond was meant to survive, even if he has to bear with the survivor’s guilt and shake it off occasionally. He can mature, but he can never get old, as author and former Ian Fleming Foundation member John Cork once said: “Bond is, in the long run, timeless. He is old enough to be a seasoned professional, yet young enough to be in top physical condition”. One could argue that the Fleming novels spanned 12 years and this made it easier to keep him somewhere between the age of 35 and 38, but the grace of the films is that the character has rarely shown a sign of ageing beyond the 40s.

The first of James Bond’s gun barrel sequences, with Bob Simmons standing-in for Sean Connery in an animation used for the first three films in the series. From 1965, each actor shot its own version and the barrel design suffered many changes.

Producers Albert R Broccoli and Harry Saltzman understood this timelessness of Ian Fleming’s character to perfection: instead of giving credit to the notion that Bond is old-fashioned and could only live anchored to the 1950s or the 1960s through period-piece films, they made him relevant to the 1970s and 1980s without betraying his essence. Even current producers Michael G Wilson and Barbara Broccoli did it brilliantly in the 1990s and the 2000s, unfortunately leaning on the Marvel type of field with follow-ups, reboots and retcons in the 2010s.

“The world changed, but Bond didn’t” was screenwriter Bruce Feirstein’s mantra for the relaunching of the series with Pierce Brosnan in 1995’s GoldenEye, a notion kept by director Martin Campbell when he rewatched the preceding films and sustained that it wasn’t necessary to change what the character was because it enamoured millions of people all over the world this way.

Despite Daniel Craig’s James Bond was turned to ashes in a quicker way than Sean Connery’s Bond almost did 51 years ago when trapped alive inside a coffin in the Slumber funeral parlour in Diamonds Are Forever, the end credits of No Time To Die still announce that “James Bond Will Return”. Unfortunately, I’m not that optimistic about that return for many reasons related to the way Bond is conceived by the producers.

Normally, one would say that they would reboot the series again or maybe that this ending was just a cliffhanger to introduce a new actor in an original way. But whatever they do, No Time To Die has hurt the image of the character much more than any financial flop.

Despite the dramatic nature and the twists to the formula that Licence To Kill (1989) suffered, Timothy Dalton’s James Bond had his much deserved warrior’s rest in the arms of Pam Bouvier (Carey Lowell).

Due to coronavirus and troubled production, the film took more than five years to get to theatres, almost the same time as the infamous gap that separated Licence To Kill and GoldenEye. The last Timothy Dalton film didn’t prove to be successful at the box office or as well regarded in 1989 as it is now, but despite the overabundance of violence and a plot that married personal vendettas with drug trafficking, Dalton’s Bond exited the scene victoriously, as one would expect of 007.

Waiting for GoldenEye was hard, but the producers proved that despite the world has changed by 1995, Brosnan’s Bond could still echo the best antics of his predecessors and not only attract old fans but create a new wave of 007 enthusiasts. In other words, we waited six years to see Bond victorious again and the numbers of Licence To Kill were soon forgotten, along with those who said the character had no place on the verge of a new millennium.

In the past 30 years, people were insisting that Bond was over, but EON contradicted them, and not just with box office figures, but by placing the character in these times and making him mightier than ever. In 2021, EON finally proved them right and delivered a movie that shows a world without James Bond. In GoldenEye, Bond has beaten modernity besides the title satellite weapon and the treacherous 006; in No Time To Die, modernity has beaten Bond along with Safin and (surprisingly, or maybe not) missiles fired by the Royal Navy where he belonged.

To me, the sole admittance that there could be a world without James Bond, even if then the character is rebooted somehow, hurts way more than any commercial or critical failure. As the saying goes, “You are never lost until you admit you are lost”. And here, EON admitted their character had lost.

The Man With The Golden Gun (1974): Roger Moore may not have been the deadliest Bond, but assassin Francisco Scaramanga (Christopher Lee) regarded him well enough to have his manikin exhibited on his hideout, along with Al Capone and other famous figures.

And in these times when the producers take more than four years to produce a film, the ending of No Time To Die falls flat on its face, particularly as the diamond jubilee of the film series is celebrated in 2022. Barbara Broccoli has recently said “it’s going to take some time” to find a new actor, yet her recent films took a lot of time even with Daniel Craig locked in the role or just by trying to convince him to return.

Had the continuity of the Ian Fleming novels On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, You Only Live Twice and The Man With The Golden Gun had been respected somewhere in the 1960s or 1970s, when Bond films came every one or two years, a cliffhanger with Bond’s apparent death wouldn’t have hurt too much.

I don’t know for certain who had the idea of killing off this version of Bond, although Daniel Craig has repeatedly said it was his idea and Barbara Broccoli went for the deal. He also insisted that the idea came to him in 2006 as Casino Royale hit theatres, but it’s very unlikely considering the reboot arc of Bond was clearly made on the way: notice how the “everything has led to this” tagline from the No Time To Die trailers were also used in some SPECTRE TV spots, or how it turned out that Silva from Skyfall wasn’t a freelancer but a member of the Quantum organization that turned out to be SPECTRE and Blofeld was behind it all, including the death of Vesper in the film that opened this era.

Whoever came up with this idea, was permanent damage. I don’t want to be that person saying that James Bond is over, and I know that somehow EON will exploit the trademark in the future, considering their other films like The Rhythm Section and Film Stars Don’t Die In Liverpool weren’t precisely successful. Bond is their golden goose. But what we can all agree on, or at least many will agree with me, is that the magic is over. Once you see James Bond dying, you don’t see the character in the same way.

It may be too late to say this, but James Bond must survive. Always. He isn’t a tragic hero or a doomed character. On the contrary, he is full of life in a context of death and loss, his lifestyle proves it better than anything.

As someone once said: “Stop getting Bond wrong!”

Brilliant article, perfectly justified and a lesson to those who speak in the name of Fleming with wrong facts. NTTD did not only kill Bond off, but it killed the franchise for good. At least we have the pre-Craig movies to celebrate the 60th somehow. Thank you!

Thank you for your words, David. Exactly how I feel it. Quoting Humphrey Bogart: “We’ll always have our GoldenEye”.

Did James Bond die so Daniel Craig could get an Oscar nomination ?

Probably that was part of the plan, since the FYC ads issued by MGM suggested Craig for “Best Actor”. Their attempts to seduce the Academy, what the producers have been trying since 2012 at least, failed miserably and they only got the usual “Best Original Song” award, which was more because of Billie Eilish than Bond. Cubby and Harry didn’t care for Oscars. They were thankful whenever a nomination or win came, but they put their loyal fans first.

Probably that was part of the plan, since the FYC ads issued by MGM suggested Craig for “Best Actor”. Their attempts to seduce the Academy, what the producers have been trying since 2012 at least, failed miserably and they only got the usual “Best Original Song” award, which was more because of Billie Eilish than Bond. Cubby and Harry didn’t care for Oscars. They were thankful whenever a nomination or win came, but they put their loyal fans first.

Comments are closed.