Released in December 1997, Pierce Brosnan’s second James Bond outing Tomorrow Never Dies dealt with the use of mass media and technology as deadly weapons. The plot was less political, intricate and suspenseful than Brosnan’s Bond debut GoldenEye in 1995. Nevertheless, Roger Spottiswoode’s film is an intense, dynamic and highly entertaining production that follows the 007 formula quite closely and adapts it to the late 1990s.

The main themes of the movie are quite relevant, twenty-five years on: how many times have we felt there is “something” behind those media barons? Tomorrow Never Dies delivers exactly this: Elliot Carver (Jonathan Pryce), a media tycoon plotting to provoke a war between the United Kingdom and China to gain exclusive broadcast rights in the most populated country in the world, for which he executes the sinking of a British warship and steals a cruise missile from its remains before trying to launch it over Beijing.

All of these themes are interestingly blended in Daniel Kleinman’s main title sequence for Tomorrow Never Dies, over Sheryl Crow’s main title song –written by Mitchell Froom and nominated for a Golden Globe award– which seems to be written from the perspective of the ill-fated Paris Carver (Teri Hatcher), the villain’s wife and former girlfriend of Bond.

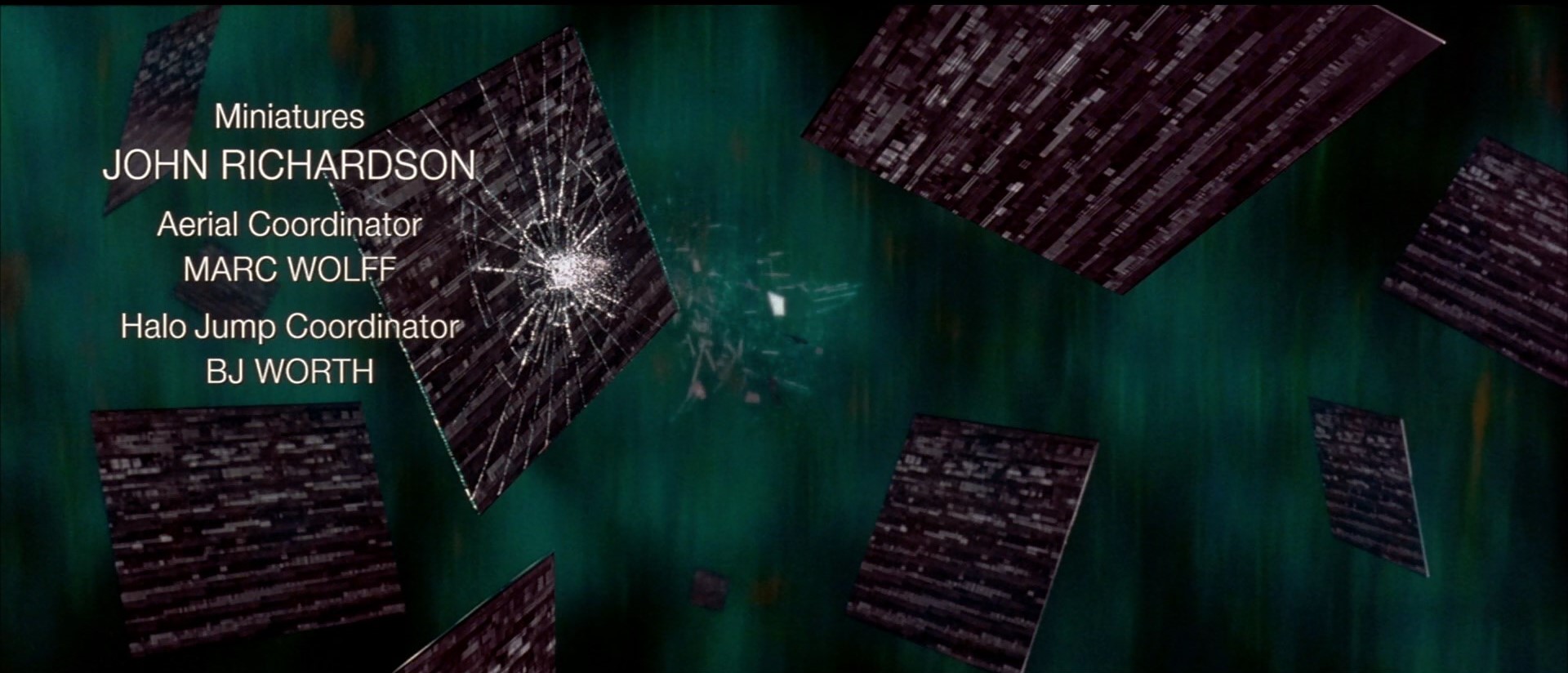

Right after Bond avoids a catastrophe that would make “Chernobyl look like picnic” on the Russian border, he activates the afterburner of the MiG jet he pilots. The afterburner’s fire causes the screen to shatter like glass – like the glass of a television screen. The rest of the sequence will take us inside a sort of cyberspace, what is inside “the box”: we fly through beams of light, programming codes, and a succession of different screens showing footage from news archives. None of them can be clearly seen, but the one that particularly stands out when freeze-framing belongs to a tank going through the streets of China in 1989, during the Tiananmen massacre: a confrontation between armed forces and civilians. Could this be a projection of Carver’s plan succeeding as well? A post-war massacre leading to the de facto government of his associate General Chang, the Red Army officer that guaranteed him the coveted “exclusive broadcasting rights” if he rose to power?

It’s not curious that this image is the only one that is clearly (or almost clearly) visible during these rapid flashes of news footage, which represents the idea of the news as a man-made “fabrication”. Never forget that, while these events did happen, the news is reported from a perspective and a man with a camera –and a whole team behind him– decide what to show and what to hide: in other words, how to emphasize drama and tension to provoke an emotion in the viewer. This is particularly noticeable in wars. Carver himself, in the film, changes the headlines of an event he staged from “British sailors killed” to “British sailors murdered” to create a stir in public opinion.

As the image liquefies, representing the liquid crystal behind a TV screen, we see silhouettes lying on a transparent floor, behind a white roof. On closer inspection, these are naked girls, but they could resemble insects or cockroaches at a glance. Just like the black-and-white illustrations shown by psychiatrists to their patients. Cockroaches are perceived as disgusting and dirty, and women as beautiful and clean. Two opposite things are equalled by the magic of television. The production of a TV show can alter how people look in real life: younger, fitter, prettier.

And with that, Sheryl Crow performs the first sentence in the song: “Darling, I’m killed”. This way, the American singer anticipates that she talks from the perspective of a woman who speaks from beneath the grave. A woman that has been murdered: she says “I’m killed”, instead of “I’m dead”. Paris Carver is killed for betraying her husband by Doctor Kaufman. Crow continues: “I’m in a puddle on the floor, waiting for you to return”. Paris approaches Bond –who had a minor confrontation with Carver’s goons– and both have a romantic interlude, in which she reveals to him how to sneak into her husband’s offices in Hamburg. As a consequence of this, when Bond returns to his hotel room after the job is done, he finds her dead body. These initial verses can be interpreted as Paris giving an omniscient view of things, waiting for Bond’s return to find her (or her body, in this case).

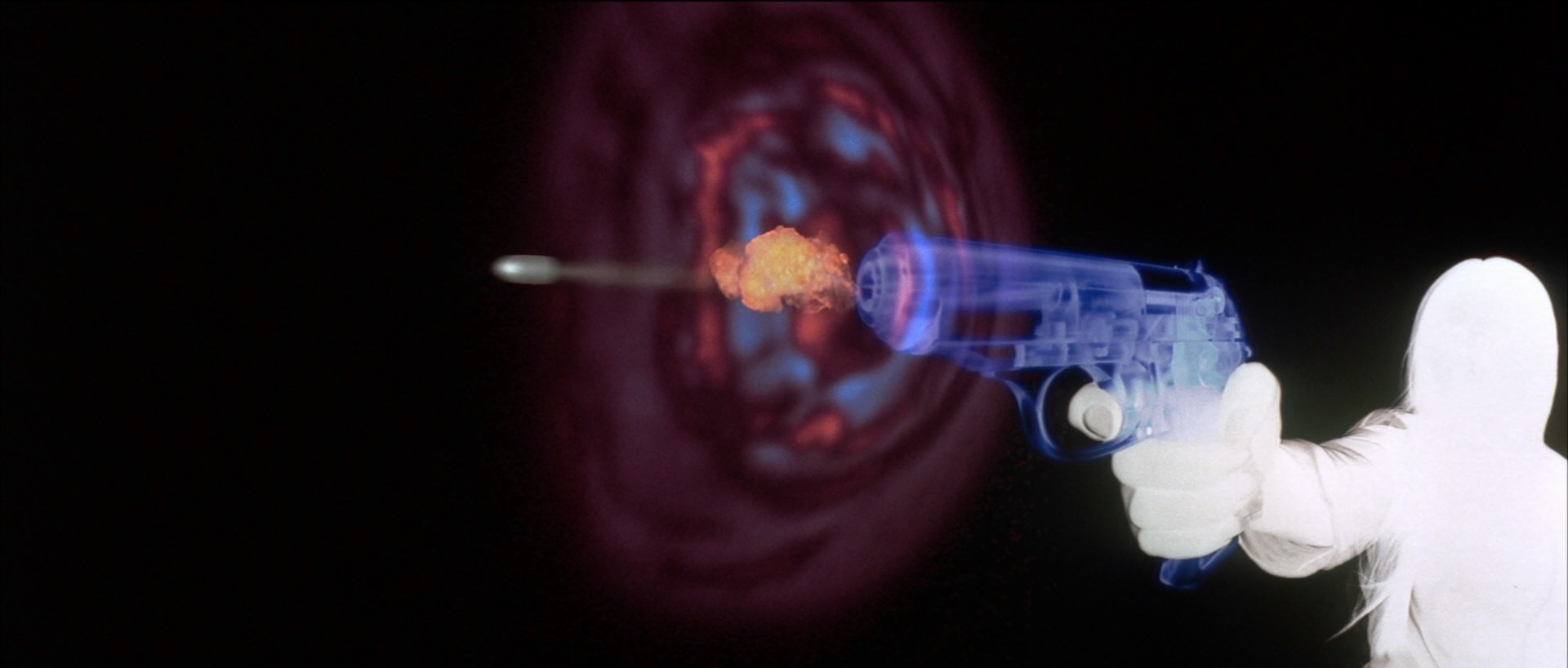

Kleinman teases us with some of Bond’s tools of the trade: his Omega watch and his Walther PPK handgun go through an x-ray filter, so we can see the mechanism of both. Paris can now see beyond things since she’s no longer with us. She can see beyond Bond, beyond the objects that identify him so much, almost as an extension of his body. From another point of view, the x-rays can be an analogy to Elliot Carver’s reach: technology allows him to reach the unreachable side of things, and he can also see “beyond” what Bond apparently is: due to a slip-up by Paris, the media mogul finds out 007 may not be a banker and uses his technology advisor to do a check-up on his cover story, concluding he is a government agent. This man, Henry Gupta (Ricky Jay) uses a security camera and isolates the ambient sound, detecting a conversation between Bond and Paris during Carver’s inaugural party: “Do you still sleep with a gun under your pillow?”. This will prove fatal to Paris, but it also proves how far the villains can reach with the use of their advanced technology. They can see beyond what we perceive.

“Oh, what a thrill. Fascinations galore. How you tease, how you leave me to burn.” Paris allows herself an irony on Bond’s cavalier attitudes he had in the past. Long before she married, they shared some happy times, but 007 couldn’t tolerate the burden of a relationship. So, he said “I’ll be right back” and disappeared. In this life, she was broken-hearted by this attitude. Now, in the afterlife, she is beyond this and takes it as “a thrill”.

Seen again through an x-ray filter, the bullets are loaded in the magazine of a Walther PPK magazine. Inside the bullets, girls are dancing. A female hand cocks and holds the weapon, but she doesn’t shoot. She just turns around and leaves, fading away. Paris forgives and just disappears, maybe?

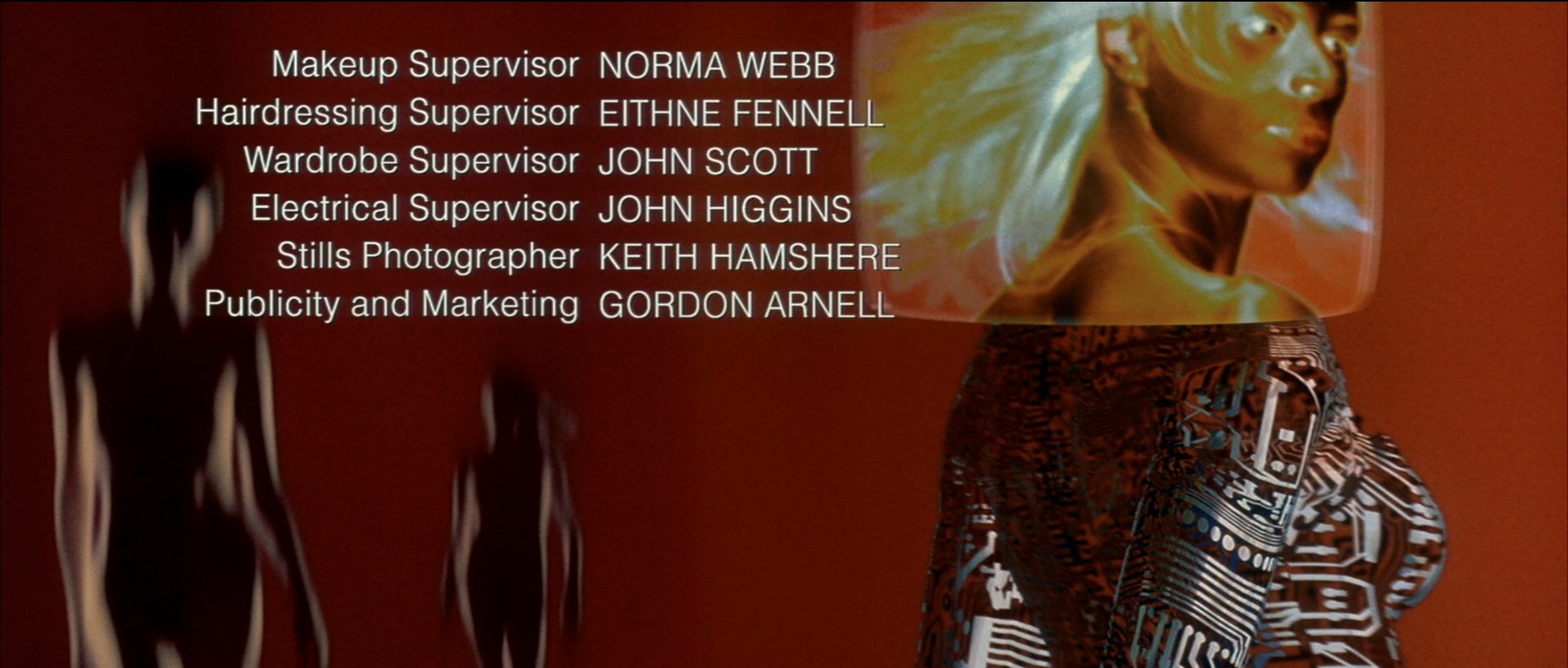

The animations move to a red circuit board, where the face of a woman begins to morph. The Missouri-born performer sings: “It’s so deadly, my dear, the power of having you near” and Paris acknowledges that having Bond close to her was something intense but dangerous. And so, the circuit boards become three-dimensional, taking the shape of a hairless, voluptuous, robotic woman. It is only when screens pass through her that her face becomes sculpted and strands of her hair wave through the air. Television, one of the villain’s many weapons (“Words are the new weapons, satellites the new artillery”), delivers what the consumer is looking for, what is commercially attractive: pieces of circuit boards, insipid and unattractive technological “junk” are shaped into sexy-looking girls, whose beauty is enhanced –or fabricated– thanks to the magic of entertainment.

“Until that day, until the world falls away. Until you see there’ll be no more goodbyes.” Paris warns Bond about an inevitable doom: the day the world will implode. The hero, Bond, is among the living, a man of this world, a warrior in this battle. He cares about the world’s safety. The villain, Carver, wants to cause havoc and destruction with his headlines and weapons to increase his power and wealth. Paris, the object of desire between the two, is among the dead and far of these men with their earthly problems. She sees the world will eventually destroy itself and alerts Bond of a day where there will be “no more goodbyes”, where it will be too late for everything. “I see it in your eyes… tomorrow never dies”. For Bond, there is always a tomorrow. Paris, however, is in a timeless place where the cares of mortals are small and irrelevant.

The main title graphics show a woman walking through a white background, where several weapons are displayed: the Walther PPK, a Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine gun, an M16 assault rifle and a Fairbairn-Sykes knife, all through the x-ray filter. This silhouetted woman fires a shot from a digitalized blue PPK, which destroys different TV screens and anticipates Bond’s victory over the villain’s mischievous plan and his empire.

“Darling you’ve won, it’s no fun. Martinis, girls and guns, it’s murder on our love affair. But you bet your life, every night, while you’re chasing the morning light. You’re not the only spy out there”. Crow sings this after the TV screens have been broken. Smoke –resembling a dancing girl– steam from the muzzle of a PPK. The mouth of another woman blows it away.

This represents that Bond has triumphed over Carver (“Darling you’ve won”), yet Paris is not necessarily impressed now (“It’s no fun”), because this partially happened at the cost of her life. She complains about Bond’s antics. We will hear later in the film that she tells him that his job “is murder on relationships”, but in this thoughts from the afterlife, she makes it extensive to Bond’s popular lifestyle, which is “martinis, girls and guns”, his vices and tools. The title animations deal with two of these elements: girls and guns, the expensive watch replacing the Martini, in this case. Paris diminishes Bond’s doings as the actions of someone who “bets his life” while “chasing the morning light”: the quest for an impossible ideal, a world order that will never exist. She emphasizes that he is not the only one doing the same job, therefore not some kind of a saviour. This vision contradicts the concept we have of James Bond: someone who will save the world. But it’s necessary to remind that Paris is beyond all that, she looks at the events from out of the picture, which grants her a different perspective: she can see that 007’s doings, on a large scale, won’t change much; and that he could have left this to others and stayed with her.

As the main titles come to a close, the robotic girl appears and Kleinman passes three screens around her body: one of them is about to pass through her breasts, but disappears right before it shows an intimate part of the female anatomy. The teasing of television and entertainment, of which James Bond itself (not as a character, but as a product) has dealt with for decades: we never see nudity in the films to ensure a PG-13 rating, but there is always enough skin to show in a girl to make it appealing to a male audience: sex scenes in the franchise are generally suggested through post-coital moments and Bond’s arms or a blanket are always covering the intimate parts of a girl.

Regarding the song, previous verses are repeated. But this time, Crow (or Paris) makes a switch in an earlier sentence: “It’s so deadly, my dear, the power of wanting you near”, instead of having. The song started with Paris talking about having Bond close, now she talks about wanting him, because they are apart: he’s alive, she’s dead.

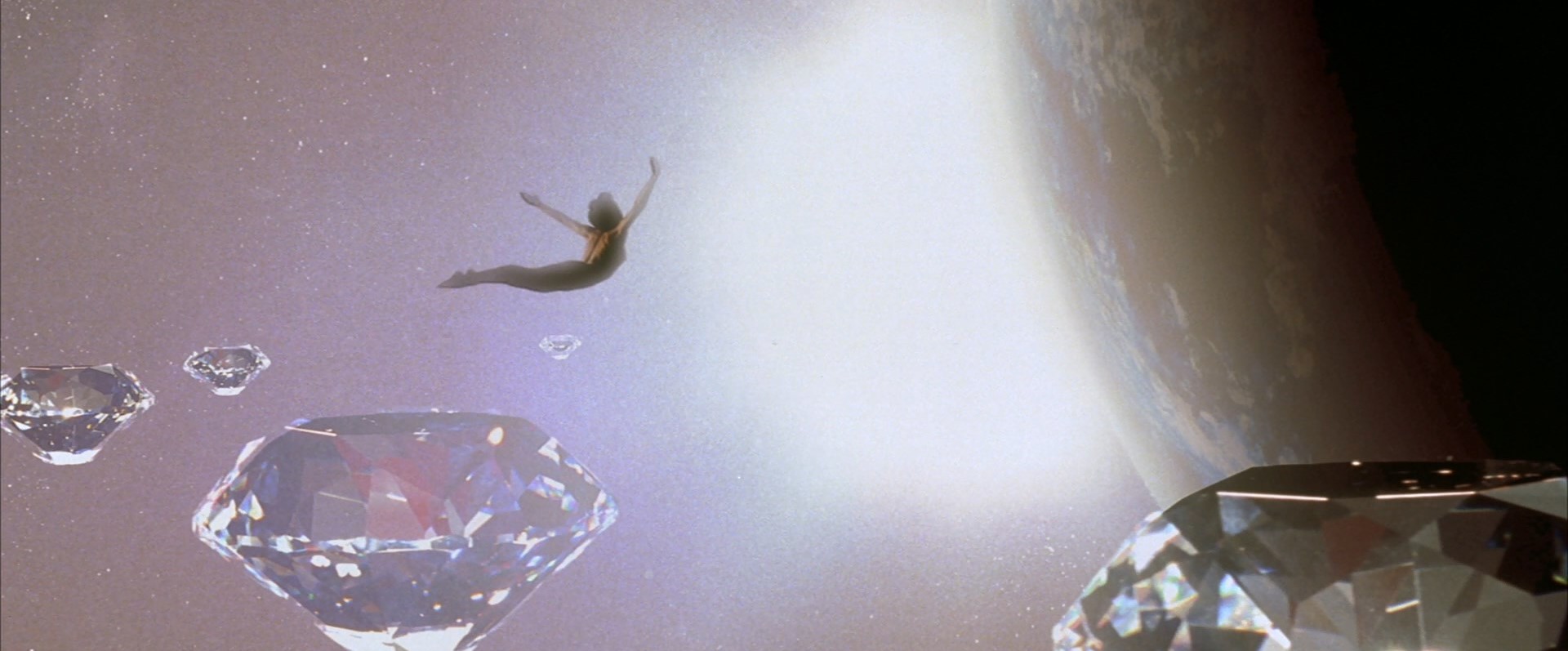

Crow repeats the chorus (“Until that day, until the world falls away…”), and we see a close-up of one of the circuit-board girls: the screen passes in front of her face, morphing her into a beautiful, hazel-eyed blonde girl with a diamond necklace. The diamonds detach from her neck and expand from each other, becoming satellites to her face. As the picture darkens and a night sky is used as the background, a bright moon emerges from behind the girl’s head. The singer performs “Until you’ll see there’ll be no more goodbyes”, and a naked girl standing on one of these diamonds jumps away as if a swimming pool was below her. The camera follows her body as she falls through cyberspace, arms wide open, surrendering and immersing herself in this attractive, fabricated, somewhat exaggerated world.

Between blue rays, static and lights, she heads right to another TV screen where the face of a suggestive brunette can be seen. She submerges on the liquid screen, between the eyes of the girl on the screen.

We understand that when Bond ditched her before the events of the film, Paris was attracted to Carver’s wealth and charisma but deep inside she didn’t feel comfortable with this and she ended up being a mere decorative element of a powerful man. When she reencounters and makes passionate love with 007, he delicately undresses her, letting her Ocimar Versolato black fall to the floor in a tide of passion, he is stripping her from a false illusion of happiness and recovering her former self: initially, she tried to show Bond that she has moved up in the world and that she made her bed and he won’t sleep on it anymore; however, Bond makes her feel like a woman again through passionate, caring sex: “I missed you,” she sighs. Therefore, this naked girl jumping to another TV screen serves as an analogy to a spectacular, visually attractive doom: getting reacquainted with Bond led her to her death, but a life with Carver was like a masqueraded, spectacular living death: a slow, silent death through the extravagance of mass media and visual effects.

After ordering her assassination, Carver pretends to camouflage the murder framing Paris as a victim of “foul play”, killed by another man who committed suicide with a self-inflicted gunshot. Bond was supposed to be that man, had Dr Kaufman succeeded in killing him, but a cleverer 007 eventually made him the protagonist of that forged story.

The sequence fades to black and we get the director’s credit over the first shot of the resumed film, the HMS Devonshire sailing through the South China Sea.

Some see Tomorrow Never Dies as a fantastic James Bond film that interpreted the classic formula better than any of the films that followed it; others see it as a downgrade from the elaborated plot of GoldenEye and the sharpness of its action sequences and twists. Still, it is hard to deny that it is one of the most entertaining and re-watchable Bond films in the past decades. And considering the relevance of the themes dealt with in the story, Tomorrow Never Dies deserves a closer look with each passing year.