Part 2 of our ongoing series exploring the ultimate action movies from the legendary John Carpenter.

Welcome back to the Carpenter series! You can find part 1 of the series on Assault on Precinct 13 here.

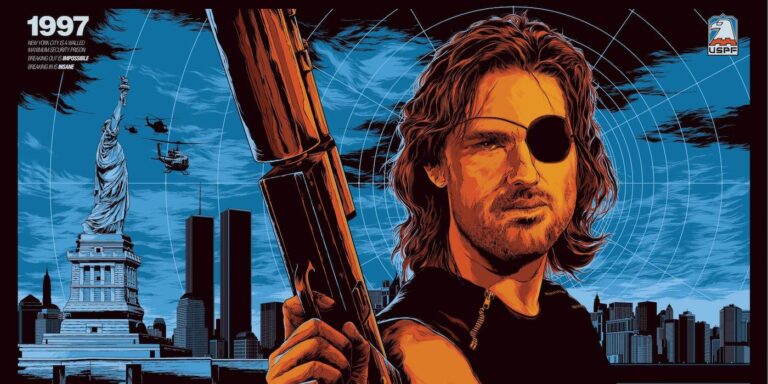

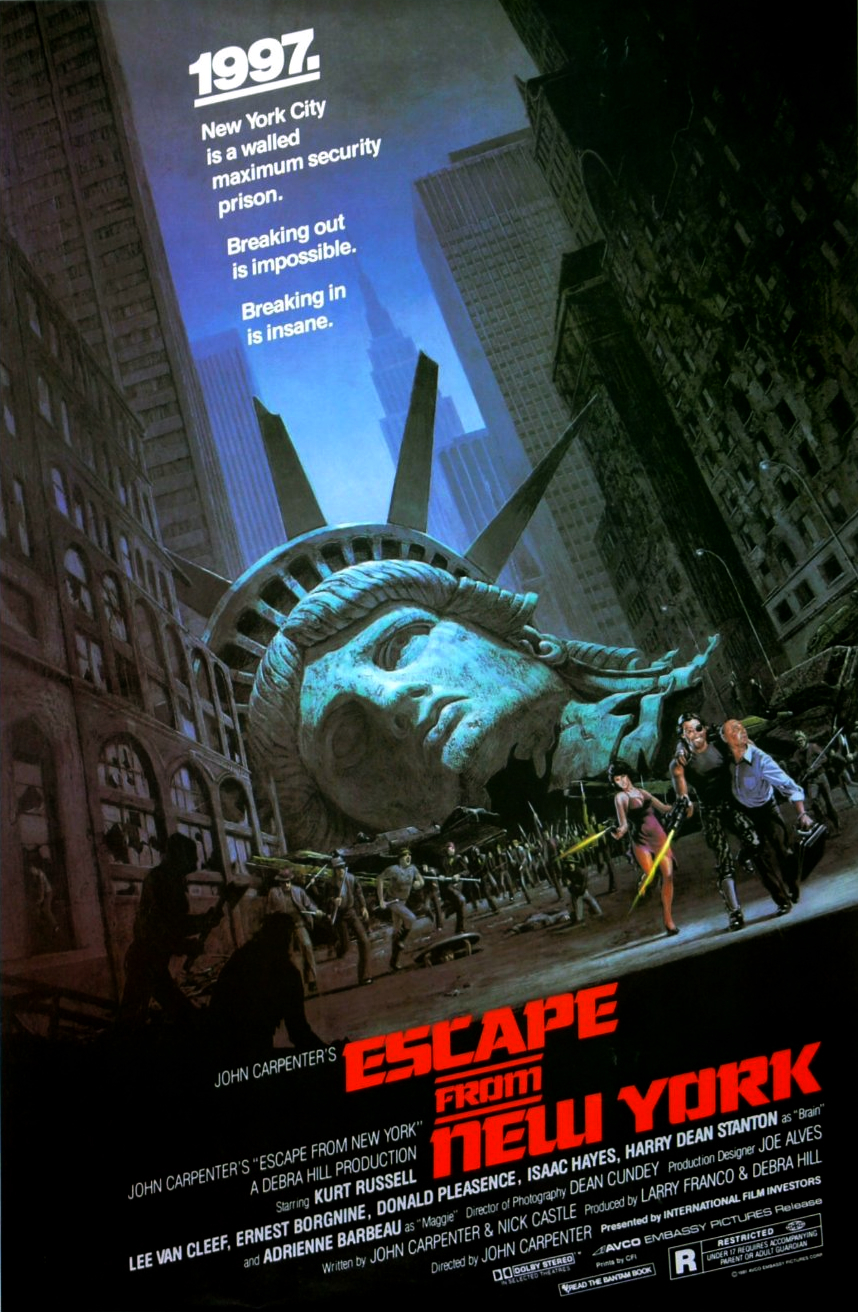

This week we look at Escape from New York.

“There was an accident. About an hour ago, a small jet went down inside New York City. The President was on board.”

“The president of what?”

Throughout Escape from New York, we never find out what pushed Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell) to go from a decorated war hero to committing federal crimes. Perhaps he’s the end result of someone who has stopped believing in America. Carpenter shows us a dystopian world set in 1997 that reflects his own lived experience post-1970. This was a decade with Watergate and the end of the Vietnam War, so it was not too difficult for audiences to connect with Snake’s rugged individualism and distrust of authority.

UAMC Reviews ‘Escape from New York’

Films in the ‘70s like Death Wish, Taxi Driver, and The Warriors all portrayed New York City with the same societal decay, covering the streets in grime and darkness. Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey took these ideas and imagined what they would look like 20 years into the future, creating an environment filled with danger and crime rates so high, that America gave up on the city entirely and turned Manhattan into a prison island.

A day before the international summit, Air Force One is hijacked by the National Liberation Front in protest against the American imperialist police state. The plane crashes in Manhattan with the president as the only survivor. Snake couldn’t care less about the president, the summit, or the potential to save the world from total war, but Police Commissioner Hauk (Lee Van Cleef) persuades him to embark on a rescue mission in exchange for a presidential pardon.

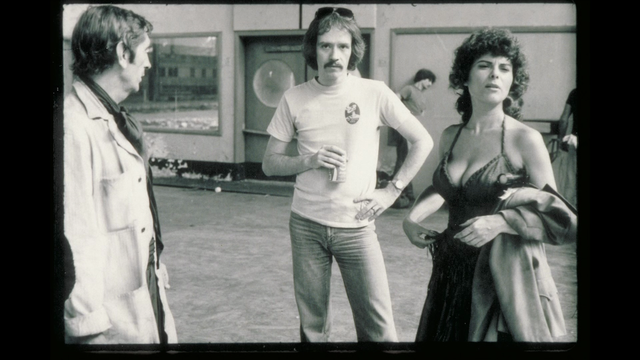

Kurt Russell and John Carpenter Together

Escape from New York marks the first theatrical film collaboration between Carpenter and Russell. Here, Russell transformed himself from a Disney star to an action hero by drawing from Clint Eastwood’s performances in westerns like A Fistfull of Dollars to create a character who says little and wears a permanent scowl, yet expresses everything with his eyes. Even more so, he inherited the antihero persona with a comparable disillusionment with the world he lives in. Much like Assault on Precinct 13, the film itself also plays like a western where much of the action is in building tension rather than extended set pieces, making scenes such as the gladiator match much more impactful.

In Manhattan, Snake learns he must face off with the Duke (Isaac Hayes) to succeed in his mission. Carpenter draws parallels between the Duke and the president, with both holding a similar disregard for the lives of others – the Duke in his brutality and the president with his dismissiveness of the people who gave up their lives to rescue him. Snake also finds signs of humanity in others, including Cabbie (Ernest Borgnine), a taxi driver who seems to have carried on with his cheerful life despite the circumstances. One notable scene is when Cabbie casually lights a Molotov cocktail and throws it at nearby Crazies in mid-conversation with Snake.

Someone Invented a Real-Life Version of Roddy Piper’s Sunglasses From ‘They Live’

But, How Ultimate is it?

Through these characterizations, Carpenter makes a distinction between societal decay among individuals and the institutions that preside over them. The film portrays its characters along an entire spectrum of morality but institutions such as the justice system and police state as having completely failed. Carpenter’s anti-establishment sentiments began with Assault on Precinct 13 and will be fully realized in 1988’s They Live. Here, he shows us that the cruel world we are presented with is justified by the rise in crime. However, the only crime we’re told is Snake’s robbery in the form of violence against property. Every plot element – the National Liberation Front, Snake’s robbery, and the militarization of the police – reveals the value of property over people. In the film’s world, and in reflection ours, America is built on this very idea.

The relationship between people and property is reflected in the final scene, where Snake asks the president about his feelings on the people who died rescuing him. Carpenter condemns the president in his belief that people are expendable property, and Snake punishes him by switching out his tape with Cabbie’s showtunes. Carpenter and Snake believe that this America isn’t worth saving. Instead, the world should perhaps follow in Cabbie’s footsteps and try to get back to a time when we could all listen to happy songs together.