How Deep Cover reminds us to never stop confronting present injustices, so that we can challenge for a more ultimate future.

Article by Alex Nguyen.

Russell Stevens Jr. (Laurence Fishburne) is a Cleveland cop who is assigned to go undercover as a drug dealer named John Hull. He is tasked to infiltrate the Los Angeles drug syndicate whose chief importer is the nephew of a prominent Latin American politician.

However, before Russell was a cop, he was a young boy who witnessed his addict father (Glynn Turman) shot down while robbing a liquor store. Russell is weighed down by this memory throughout his life, and he swears to never be like his father.

Deep Cover as a Subversive Neo-Noir

Deep Cover takes many elements from film noir and subverts them to examine how black communities are affected by American society. Film noir is a genre from the post-war 1940s that rose from a heightened anxiety towards evolving societal perceptions of racial, gender, and class dynamics. It portrays detectives shot with voiceover narration and chiaroscuro lighting to depict an inherently corrupt world mired in moral ambiguity. The detective would often clash with politicians, the upper class, and their respective institutions. However, where classic film noirs only hint at contradictions between what our institutions promise and what they actually do, Deep Cover goes a step further and explicitly shows them enacting violence against black communities. It directly engages with the war on drugs in American cities and its connections to Latin America, U.S. politics, and the disproportionate criminalization and death of African Americans.

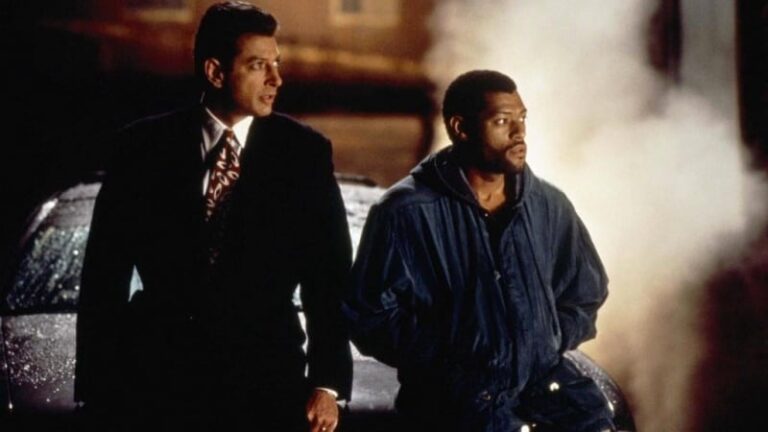

Russell’s trauma over his father’s death imbues him with a sense of virtuousness. He becomes a police officer with the idealistic intention to help his community by taking crack off the streets. While undercover, Russell transforms into John and rapidly ascends the drug ring. Russell teams up with David Jason (Jeff Goldblum), a lawyer also looking to climb the ladder to make a lucrative business developing new designer drugs. Director Bill Duke immerses the audience in an infectious atmosphere, almost willing them to want Russell to succeed in his ascension. However, there is a sudden tone shift when Russell is forced by the rules of the street to kill a rival (James T. Morris). Cinematographer Bojan Bazelli shrouds Russell in blood red light as a warning for the world of violence Russell has entered. Despite his intentions, Russell becomes a tool for the state against the very people he was trying to save. “I had killed a man. A man who looked like me. Whose mother and father looked like my mother and father. Nothing happened.” His idealism begins to crumble, and he struggles with his complicity as a black man and a pawn within the police system.

Laurence Fishburne as Russell Stevens Jr.

As Russell grows his business, he descends further into darkness. He becomes partners with David, and he begins to live the part. He gets a new apartment, a new car, and a new girlfriend. Russell and David’s relationship comments on American racial dynamics. Deep Cover highlights the complexities in these dynamics such as when David, a Jewish man, prefers to sleep with black women and is called out by Russell for enjoying the dominant aspect of a projected racial hierarchy. The film also provides some sharp political commentary about the relationship between the police, crime, and government. A corrupt police officer begs Felix (Gregory Sierra), a mid-level supplier, to give him a drug bust to alleviate suspicions. Felix offers Russell and David. “Politicians like the dark faces so they can scare the suburbs into voting Republican.” The film portrays everyone as complicit in the system that allows drugs to enter the country, the police to imprison African Americans and other minority groups, and the politicians to make profit and continue the cycle.

Deep Cover was inspired by Michael Levine’s book of the same name. It is an account of how, in the 1980s, the DEA conducted undercover operations involving Latin American drug trafficking into the United States. The film specifically names Manuel Noriega, a Panamanian politician that was the country’s de facto ruler from 1983-1989. He had long ties with U.S. intelligence agencies and acted as a conduit for illicit weapons, military equipment, and cash for U.S.-backed groups throughout Latin America, including Contra rebels in Nicaragua and the authoritarian government in El Salvador. The film’s acknowledgment of Noriega and his relationship with George H. W. Bush was particularly incendiary as it was released in the same year as the 1992 U.S. presidential election. It also highlighted the alleged involvement of the CIA and resulting profit through the Nicaraguan Contras’ cocaine trafficking into the United States. Through the illegal drug trade, the U.S. exchanges black lives for monetary profit, political gain, and greater world influence.

But How Ultimate is it?

The same societal problems that Deep Cover examines are still very much present today. Just last year, there were Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others. It was also characterized by police violence in retaliation to these same protests. Social media feeds were filled with videos of togetherness and solidarity as well as the police brutality that threatened to tear it all down. It would be easy to be overwhelmed by all of it and tune it out. To a certain extent this is necessary, but the film urges us to confront our own relationship and complicity with a system that directs violence against black communities, or else the system will continue ad infinitum.

Towards the end of the film, Russell learns that the U.S. State Department is pulling their project as they want Hector Guzmán, the Latin American politician, to be a political asset in the future. This breaks Russell as all the work he has done and concessions he has made were for nothing. He abandons his undercover status and decides to take down Guzmán alone. Despite the film’s weariness over this endless cycle, it subverts the noir genre one last time. Instead of ending with the protagonist either dying or facing tragedy, the film ends with Russell prevailing. While he was unable to change the entire system from the inside, he was able to at least create a disturbance by recording Guzmán’s involvement in drug trafficking, thus ending his lucrative political career. Deep Cover defies classical film noir conventions to contemplate how the U.S. silences black people as they hope to change their own stories to not be repetitions of their pasts. In doing so, Deep Cover reminds us to never stop confronting present injustices, so that we can challenge for a better future.

Fantastic! I never even heard of it…!

This is exactly the kind of movie I enjoy watching, thank you for writing about it.

I love this site.

Comments are closed.