A James Bond essay on ‘GoldenEye‘ and the relics of the cold war.

GoldenEye set the foundations for what Ian Fleming’s character should be in a post-Cold War era, on the road to the new Millennium and with new threats coming after the 9-11 attacks

GoldenEye was the first James Bond film to be released after the fall of the Berlin Wall and, therefore, the one that put an end to a much-beloved tradition in the legendary series where the Russians were the enemy or, actually, believed to be the enemy. The film saw the light on November 13, 1995, at the Radio City Music Hall of New York City, where thousands of celebrities, journalists and guests gathered to see the long-awaited return of Ian Fleming’s secret agent to the big screen, after a six-year-and-a-half hiatus which began after the poor numbers of 1989’s Licence To Kill and a legal conflict between Danjaq and the businessmen taking over MGM/United Artists in the early 1990s.

The End of a James Bond Cold War Era

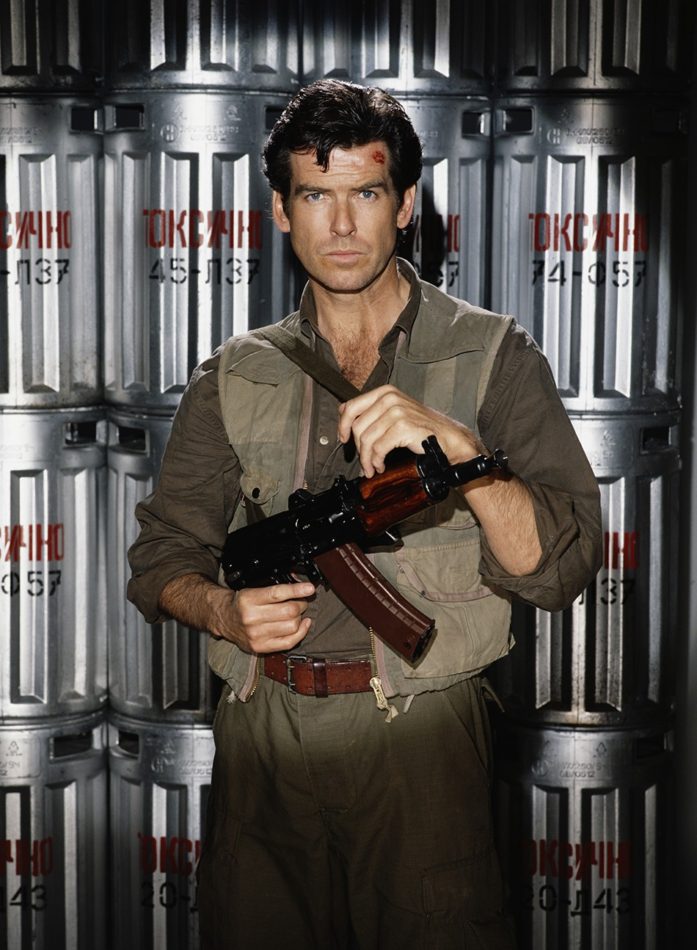

For the last time, during the movie’s pre-credit sequence set in 1986 on a desolated chemical weapons facility in Archangel, north of the Soviet Union, we saw James Bond exchanging bullets with those olive uniform troops bearing a red star in their berets and their red jacket stripes. The main title credits, designed by Daniel Kleinman on his first Bond collaboration (not counting Gladys Knight’s “Licence To Kill” song music video) served as an ellipsis between 1986 and 1995 with scantily-clad women destroying Communist symbols and statues with hammers and mazes.

And then we are in the present: agent 007 is in Monaco, races a beautiful brunette on his Aston Martin DB5, and then meets her at the expensive Casino de Monte Carlo, where he learns her name is Xenia Onatopp and comes from a new Russia: “a land of opportunities”, where she can enjoy driving a red Ferrari and other western luxuries. However, as it always happens to James Bond, the people who come across his path are rarely men or women “from the street” and the fact that Xenia’s Ferrari has a counterfeit number plate arouses suspicions.

Indeed, Xenia was an ex-Soviet fighter pilot whose trip to Monte Carlo was not for tourism. She is there to steal an EMP-resistant Tiger helicopter to be shown on a French warship the next day. Upon investigating, Bond realizes that the fall of Communism has led to bigger dangers coming from the new Russia, which would seriously compromise Great Britain’s financial future sending it “back to the Stone Age”, as the film’s villain says.

The Smart and Poignant Action of James Bond and ‘Tomorrow Never Dies’

The Complicated Allegiances of Alec Trevelyan

The villain in question was, in fact, a former friend: Alec Trevelyan, known as MI6 agent number 006 before he was killed in action during the Archangel mission. Now, he operates under the name of Janus and his activities in Russia involve arms dealing, notoriously the restocking of the Iraqis after the Gulf War. The man who shares the name with the Roman god of two faces has only two objectives: moneymaking and revenge.

Trevelyan was the son of two Cossacks, part of a bloc of the Cossack army that during World War II was led by General Piotr Krasnov and joined the side of Adolf Hitler against the Soviet Union. Eventually, they were outnumbered and went into the Italian Alps and then to the city of Lienz in Austria, where they came across British soldiers and high ranking officers. They hoped to reach a deal with the Allies, but Winston Churchill heard from Stalin’s mouth on the Yalta conference that the Cossacks “fought with savagery and ferocity” for the Nazis. That was enough for Churchill to deport them back to the Soviet Union and into the hands of Stalin. Krasnov, the leader, was sentenced to death by hanging along with other members of the group. Some of them, like Alec Trevelyan’s parents, committed suicide after escaping from the death row but unable to tolerate the guilt.

“MI6 figured I was too young to remember. And in one of life’s little ironies, the son went to work for the government whose betrayal caused the father to kill himself and his wife,” tells Janus to an astonished Bond, not believing that his friend, the one he saw dying nine years ago in an operation and has felt a pinch of guilt about it, has been actually behind it all and holds an enormous grudge against the nation he has sworn to protect.

How ‘Thunderball’ Set The Stage For The Modern Age of James Bond Action

An Affair in St. Petersburg

Not accidentally, this encounter between James Bond and Alec Trevelyan takes place on an abandoned park in St. Petersburg, surrounded by debris and remains of Soviet statues torn down. The location, recreated by production designer Peter Lamont on the improvised Leavesden Studios (former Rolls Royce factory), underlines the fact that ideologies are dead and patriotism is an antiquated fashion. Moneymaking and free-market economy is above it all and it brings old enemies together and places old friends on different sides. Throughout GoldenEye, the patriotism of James Bond is thoroughly questioned by many characters, namely Trevelyan and Valentin Zukovsky, once a KGB nemesis of 007 and now a Janus rival on the arms dealing business who could become a potential ally if he appeals to “his wallet” instead of his heart. “Still working for MI6 or have you joined the 21st century?” hissings the bulky Russian gangster when Bond –risking his life– comes for help. In the same way that for Trevelyan moneymaking comes above the codes of patriotism and honour, Zukovsky has “joined the 21st century” by doing illegal business after the identity of the cause the KGB was made to protect has crumbled along with the Berlin wall.

While Alec Trevelyan and Valentin Zukovsky have focused their main interest in money and don’t share Bond’s idealistic vision of justice and ethics, General Ourumov does in a way. The Russian officer who pulled the trigger of his Makarov handgun over Trevelyan’s head in 1986 firing a blank (most likely) has been severely affected by the new world order. In the words of Gottfried John, who played the role: “He tries to re-establish the old system while using the new Russian mafia to do so.” After the events of 1986 that concluded with Bond blowing away the Archangel facility, Ourumov hasn’t lost his job and was promoted from Colonel to General during Mikhail Gorbachev’s government, given the command of the Space Division.

Gorbachev’s glasnost policies in 1991 have worried a couple of fervent Soviet politicians and officers who by the end of August have staged a “State of Emergency” that was actually a covert coup led by Vice-President Gennady Yanayev as the Russian leader was taking holidays on his Crimean dacha. Eventually, the coup failed by the intervention of the President of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin and thousands of citizens who resisted this unelected and unconstitutional new government. The Soviet Union was dissolved and Gorbachev resigned. Meanwhile, Yanayev and other conspirators were arrested, while others committed suicide. One of those who took their lives away was a close associate of Ourumov, who is believed to have taken part in this coup but nothing could be proved after the suicide of this co-conspirator and the inquiries against him were dropped.

A State of Emergency

The dossier of Ourumov can be briefly glimpsed on a monitor as M briefs James Bond and it indicates his presumed involvement on the 1991 coup. While he was unaffected of suspicion, it is very likely that he has had a part on it considering that he shares the same patriotic codes of Bond. Moreover, it is noticeable throughout the story that he isn’t happy with the new wave of politicians and civilians running the country as it can be seen during his encounter with Defence Minister Dimitri Mishkin, thought to be part of Boris Yeltsin government if we consider the film is set in 1995. On the film’s novelization, published by Boulevard Books and written by John Gardner, it is established that Mishkin felt completely uncomfortable with Ourumov arriving 10 minutes late to a meeting after the Severnaya attacks. It is understood that, while Alec Trevelyan has no ideology and is more primarily interested in revenge and money, General Ourumov teams with Janus perhaps to gain power and reinstate a military government in Russia and most likely reinstating the Soviet Union with him being the leader (“The next Iron Man of Russia”, as he sees himself according to M).

Interestingly, Bond plays his card later by telling Ourumov that Trevelyan “is a Lienz Cossack” that “will betray him just like everyone else”, trying to pit one against the other when his love interest Natalya is held at gunpoint by the General. The events from 1945 come back in a short but very intense scene held on a train carriage where Bond tries to remind Ourumov that in the first place the Lienz Cossacks have betrayed the Russians in the first place and that Janus would most likely betray him just as his parents did to Stalin, aiming to the Soviet pride heart of the General.

Bond and Ourumov seem like the only ones in the film to care about a nation and ideology, while characters like Zukovsky and Trevelyan are more interested in their own business and making a life in the new Russia, now laden of technology and the vices of the West. Ironically, the pressure that General Ourumov feels from the politicians in Russia is almost the same pressure James Bond feels at the MI6 headquarters in London with the new M, a female senior analyst who calls him “a relic of the Cold War” and is far from the style of the old Admiral Sir Miles Messervy that decorated his room with paintings of naval battles. These two characters are constructed as anachronisms that are trying to find their place in a post-Cold War setting, though Ourumov finds it under the tentacles of the evil Janus Syndicate.

A Modern Day James Bond Emerges

By the early days of 1990 there was much ado about how James Bond would survive the new decade after the end of the Cold War. Although not all the movies had plots focused on the Cold War (namely On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Live And Let Die, Moonraker and Licence To Kill), the fact that James Bond had its inception in 1953 when he was sent to a casino in the South of France to beat a Soviet agent on a baccarat table in Ian Fleming’s novel Casino Royale has established him as a public enemy of the Soviet Union. Not in vain in nearly all the Fleming novels he confronts agents of SMERSH, the execution branch from the Russians. In the film, this was toned down during the hot political climate of the 1960s by having the USSR not directly being the enemy (and used for fools by the apolitical SPECTRE) or the enemy being the Red China, in association with villains like Dr. No or Auric Goldfinger.

Either way, GoldenEye served as a farewell and a last trip to nostalgia from the days Bond battled the Russians and this was emphasized by the story, which relied very much on the current times and took notice of that archetypal image of James Bond as the number one enemy of Russia. Future Bond films with Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig would focus on other interesting aspects of their times, like mass media used as a weapon, the hoarding of natural sources or, more recently in 2015’s SPECTRE, the control of spy networks.

GoldenEye set the foundations for what Ian Fleming’s character should be in a post-Cold War era, on the road to the new Millennium and with new threats coming after the 9-11 attacks. It also proved that the character could keep reinventing itself and still be relevant while retaining its essence. In the words of screenwriter Bruce Feirstein: the world changed, but Bond didn’t. This was the formula for a film that expounded in the script what every moviegoer and film critic was wondering by the time: “Is James Bond still relevant?” GoldenEye not only proved that he was, but instead of jumping from an era to another it showed how much the world has changed and how much we still needed Bond every time a new geopolitical map is configured.

Nicolas Suszczyk is the author of The World of GoldenEye: A Comprehensive Analysis on the Seventeenth James Bond Film and Its Legacy, which is now out on Amazon. He also manages the sites The GoldenEye Dossier, Bond En Argentinaand co-admins The Secret Agent Lair with Jack Walter Christian. Other writing credits include the magazines MI6 Confidential and Le Bond, as well as the sites MI6: The Home of James Bond, The Spy Command and Siete y Medio.