James Bond is not an assassin – at least not in the way we often make it to be when comparing him to other Hollywood characters.

Many film bluffs exploring the unlimited success of Ian Fleming’s secret agent James Bond through almost six decades have placed him under the category of “an assassin”.

It’s not astounding if we consider that -as the promotions for the first film Dr No reminds us- Bond has a licence to kill “when he chooses, where he chooses and whom he chooses”, and that ever since 2002 EON Production has embraced this narrative: in Die Another Day, two North Korean characters brand 007 as “A British assassin” and in SPECTRE another villain, Mr White, is reluctant to hear “the word of an assassin” when Bond comes to visit him in order to reach the man in top of him at the organization he used to integrate.

In the same film, released in 2015, the secret agent introduces himself as “someone who kills people” to Madeleine Swann, and she asks him why did he “chose the life of a paid assassin” during a romantic dinner onboard a train crossing the Moroccan desert.

Not all of this happened in the Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig eras, tough. In 1983’s Octopussy, Roger Moore’s penultimate outing as Bond, the leading lady played by Maud Adams whom the film was named after called him “an underpaid assassin” during a heated argument that ended, as you might expect, with a passionate kiss.

But does all of this really make James Bond an assassin? Being licenced to kill immediately classifies him under the same category as Arthur Bishop from The Mechanic, Léon from The Professional, Agent 47 from the Hitman film and video game series or Edward Fox’s Jackal from The Day of The Jackal, who almost succeeded in murdering French president Charles de Gaulle?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, an “assassin” is defined as “someone who kills a famous or important person, usually for political reasons or in exchange for money”. The example cited is Mark Chapman murdering John Lennon. If we take this to our celluloid characters, this description is much closer to the aforementioned characters than to 007 himself. Although James Bond does take part in assassination missions, the legal boundaries and somewhat “ethical” codes of the government branch he responds to.

Casino Royal and the Origins of James Bond

Let’s go back to where it all started: Casino Royale, Ian Fleming’s “spy story to end all spy stories” published in 1953. We know throughout the book that Bond was given the 007 designation (this famous “licence to kill”) after murdering two enemies of the country spying for the Germans, making him apt for operations where killing would be involved, be it in self-defence or not.

Yet, once we are first introduced to Bond in the novel, he is given a very simple assignment: he has to run down Le Chiffre, a banker for the Soviet agents, by betting against him in a baccarat table. Why? Because the man has been using the funds of these agents for careless gambling. Why not just kill him, if Bond is licenced to kill? The British Intelligence determines that, had Le Chiffre been just murdered, he would be regarded as a hero or some kind of martyr.

By cleaning him out of chips, he would be exposed as a fraud and that would make a hole into the Russian pride, which would eventually kill him in revenge. Some books later, in 1959’s Goldfinger, Bond reflects on having killed a hitman in Mexico with his bare hands (self-defence, in this case) and didn’t feel comfortable with it, but remembered that as a 00 he must be “as cold as a surgeon” concerning life and death

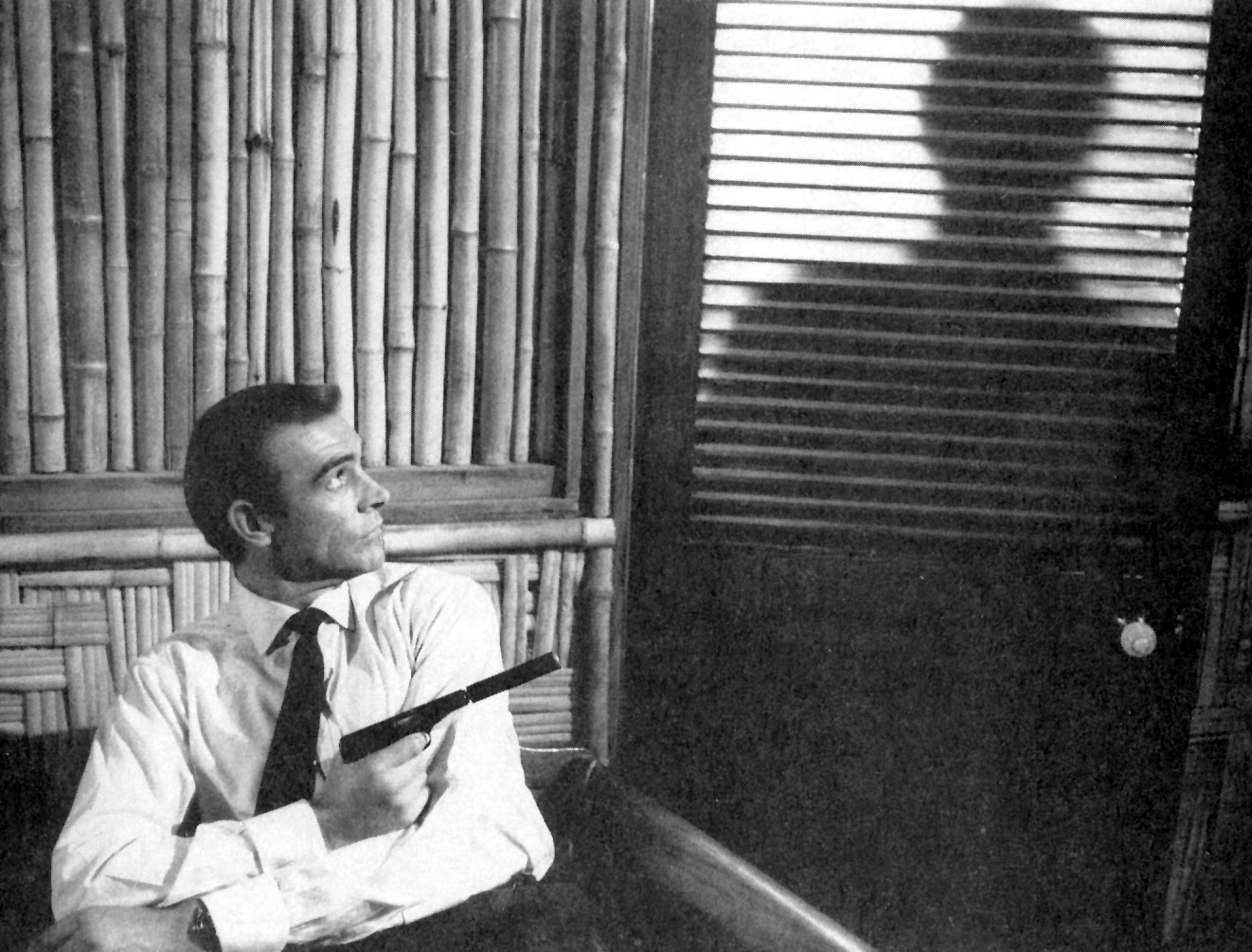

Once we get into the movies, with Dr No starring Sean Connery in 1962, we rarely see Bond been explicitly given assassination missions save for a few occasions and, in the end, 007 kills in self-defence. Unlike Léon or Agent 47, Bond isn’t given a couple of bucks and details of the enigmatic Doctor Julius No to do the job.

He is simply sent to Jamaica to investigate the disappearance of a fellow agent and ends up discovering a Red Chinese scientist is playing havoc with the rockets launched from Cape Canaveral. Bond commits two cold-blooded murders: Professor Dent, who tried to shoot him with an empty gun, and an unnamed guard patrolling the Crab Key island. He wasn’t ordered or had any incentive to do so, and the decision went on his command, mostly to show his toughness: “when he chooses, where he chooses and whom he chooses”, quoting the poster tagline again.

Although, it is necessary to underline that this promotional slogan is heavily exaggerated, as Bond isn’t allowed to murder innocents and would be tried and court-martialled if he did so with, let’s say, an annoying neighbour playing loud music at three in the morning. The evil doctor dies by falling in a vat of boiling water after an intense battle with 007 just as his secret lab was about to explode.

The following films went on by the same lines and the main villain was always killed in self-defence, or survived like Ernst Stavro Blofeld, or in the case of Thunderball was harpooned behind his back by the leading lady Domino as she tried to save the secret agent’s life when the evil Emilio Largo held 007 at gunpoint.

Something interesting happens in The Man With The Golden Gun, Roger Moore’s second Bond outing in 1974: our hero comes across an actual assassin who “charges a million a shot”, according to the film’s bombastic theme tune performed by Lulu. In fact, it is this hitman, Christopher Lee’s Francisco Scaramanga, the one who is on to Bond: he had murdered an MI6 agent once in Beirut, Bill Fairbanks aka 002, and now has sent a warning to 007. M, the leader of the British Intelligence, doesn’t even order Bond to take action: he takes him out of his current assignment and offers him to resign or a sabbatical year.

However, Bond decides to go on his own trying to “find Scaramanga first” and ends up learning that the warning was sent by none other than Scaramanga’s tortured lover, Andrea Anders, who wants to be free from him. “You need a lawyer”. “I need 007!” she insists, influenced by Scaramanga’s flattery of Bond, who sees him as some sort of an “equal”, a fellow assassin.

Near the end, the two men come across each other and challenge each other to a duel à la mort in the villain’s island, but not before sharing a delicious meal. This is perhaps the first occasion in the entire series where Bond distances himself from the “assassin” image and Scaramanga’s flattery: “Now, Come, come, Mr. Bond. You disappoint me. You get as much fulfillment out of killing as I do, so why don’t you admit it?”

The secret agent admits killing this villain “would be a pleasure”, but only after stating that when he kills is “under specific orders of his government, and those he kills are themselves killers”. Therefore, we see him expressing his contempt at Scaramanga’s pride of his profession. James Bond does kill, but he applies some kind of judgment that contract killers don’t generally have. In the case of Léon, it’s “no women, no children”, but he never stops to think if the man he cleaned was another murderer or a criminal or simply someone targeted for rather pedestrian reasons: foul play, score settlements, corporate or political rivalries, etc.

James Bond: Remembering the Ultimate Heroes Behind ‘GoldenEye’ (1995)

Timothy Dalton and Bond’s Ultimate Judgement

Another good example of Bond’s judgment that distances him from common contract killers is Timothy Dalton’s 007 debut film in 1987, The Living Daylights. In this thriller, a secret Soviet Intelligence cell is reactivated and systematically terminating British and American agents, one of them perishes during an innocent training activity at the Rock of Gibraltar (along with two SAS officers playing the “villains” in this war game).

Upon information received by General Koskov, a KGB defector, M orders Bond to kill the organization’s new leader General Pushkin. All Bond is given is a blue folder with a black and white photo of the man sentenced to death by MI6. 007 is hesitant, as he doubts Pushkin fits the profile of a psychotic belligerent man who would light the fuse this way, so M at first wants to assign the mission to 008 because “he follows orders, not instincts” until Bond insists that if someone has to do it, he prefers to do it himself.

Before even trying to put a bullet in Pushkin’s temple as any other hired murderer would do without even blinking an eye, James Bond investigates a lead: the female KGB sniper who stalked Koskov as he tried to defect, only to learn she’s actually Koskov’s girlfriend Kara and her rifle was loaded with blanks. Later, he infiltrates Pushkin’s hotel suite in Tangier, where the man was staying before a conference. Bond holds the man at gunpoint and replicates Koskov’s accusations, which he categorically denies, and reveals he was about to arrest the General for misusing state funds. “You are a professional, you don’t kill without a reason”, Pushkin tells Bond. “If I trusted Koskov, we wouldn’t be talking,” Bond explains.

Earlier in the film, while 007 was covering Koskov’s escape in Bratislava, Bond was ordered to kill the KGB sniper sent to hunt the General and prevent his defection. Upon seeing through the crosshair that she was inexperienced in the way she was holding the rifle, he opted to shoot her in the forearm instead of her head. This causes a heated argument between Bond and Saunders, MI6’s contact in Czechoslovakia, who reprimands 007 for risking the mission and disobeying a direct order deliberately. However, the secret agent insists that “he only kills professionals”.

James Bond: Looking Back at Timothy Dalton’s ‘Licence to Kill’ (1989)

Licence to Kill or Licence Revoked?

Licence To Kill, released in 1989, underlined the limitations of James Bond’s notorious privilege used to title this production after the original title, Licence Revoked, lacked the required impact in the domestic market. In this film, Timothy Dalton’s Bond embarks on a revenge mission against drug lord Franz Sánchez, brilliantly played by Robert Davi, when this powerful man escapes captivity and launches a brutal attack against CIA’s Felix Leiter and his wife Della.

Just as Bond performs his first act of revenge, which is feeding the turncoat policeman bribed by Sánchez into the same sharks who maimed his friend, he is stopped by American agents and handed in to M, who reprimands Bond for going full Dirty Harry mode by disobeying orders and messing with the laws of the United States. The secret agent resigns and M revokes his licence to kill shortly before a rogue 007 escapes from his boss and bodyguards to go after Sánchez without support of the British government.

Timidly, M turned a blind eye at the beginning of Diamonds Are Forever when Bond searched everywhere for Blofeld and threw him (one of his doubles, we later know) in a vat of boiling mud to avenge the death of his wife Tracy, but in this case we are talking about a full revenge plan that involves going violating the laws of an allied country and a diplomatic embarrassment for MI6 should anything go wrong.

Back in the day, this was a commercial selling point for the film as James Bond, who was considered (even in the Fleming novels) as someone who never operated against the system and everything he did was under Her Majesty’s orders this time defied the authority of M and went after his organization, having both the British and Americans tailing him as he tried to infiltrate Sánchez’s big drug empire that extended from Chile to Alaska. If we were talking about an assassin or a hitman, which is the conception many have of Bond, this wouldn’t be a selling point at all, and we wouldn’t be surprised of his revenge desire. But this film certainly underlined that there is something above Bond that places him under the category of some sort of law enforcer governed by certain ethics or codes – the ones that are broken in the John Glen film.

These ethics are subtly showcased in the prologue of GoldenEye, released in 1995 and starring Pierce Brosnan as James Bond. Agents 007 and 006, Alec Trevelyan, infiltrate on an illegal nerve gas facility in the Soviet Union. As both men are heading to the storage area of the installation, Trevelyan takes a moment to shoot an unarmed scientist while Bond uses a gadget to unlock a door.

This moment would raise eyebrows between the viewers as we are meant to believe a 00 agent like Bond would be ruled under the same codes and civillian casualties must be avoided at all costs. However, throughout the story, we learn that this man Trevelyan, played by Sean Bean, is actually the villain of the movie and betrays both Bond and the Realm after faking his death in the aforementioned operation. This case of reckless brutality and unsanctioned hit served as a way to “warn” the audiences that there was something strange about this agent and shouldn’t be fully trusted. The difference between the “good guy” and the “bad guy” is underlined by the fact the villains don’t care about taking innocent lives while the hero does.

Pierce Brosnan’s James Bond is given two assassination missions in The World Is Not Enough and Die Another Day. In the 1999 film he is ordered to protect oil heiress Elektra King from the hands of Renard, the terrorist that has once kidnapped her and attacked MI6 by murdering Elektra’s father, a personal friend of Judi Dench’s M. It is implicitly understood that his mission also involves eliminating Renard, which was a threat for both MI6 and Elektra: during the woman’s kidnapping, M sent 009 to kill him, but Renard survived.

It is now Bond’s job, mostly as a personal favour to M, to terminate the man before he strikes again. He is about to do it just as Renard was about to steal a nuclear bomb from a facility in Kazakhstan, and Brosnan’s words bring back the statement expressed by Moore in The Man With The Golden Gun twenty-five years before: “I usually hate killing an unarmed man. Cold-blooded murder is a filthy business. But in your case, I feel nothing, just like you.”

Michael Apted: The Director That Set the Future of James Bond

What Does Bond do Before Pulling the Trigger?

Much like in The Living Daylights, Bond’s judgment comes to play before pulling the trigger: Renard utters a phrase that Elektra said before during a blackjack match in a casino, making Bond presume that the businesswoman isn’t as innocent as one may think and might have something in common with his former captor. His presumptions will be confirmed later when Elektra, thinking 007 has perished in an explosion, turns on M and reveals she planned the death of her father with Renard when the wealthy man stalled the payment of the kidnap.

In the pre-credits sequence of 2002’s Die Another Day, Bond takes the place of a diamond trafficker along with South Korean agents to put an end to the life of Colonel Tan-Sun Moon from the North Korean army. The plan called for 007 to detonate some C4 explosives hidden inside a briefcase carrying conflict diamonds from a distance, but a mole in the British Intelligence exposes 007’s identity and a thrilling hovercraft chase ensues through the minefields of the Demilitarized Zone, in which Bond ends up killing Moon in self-defence during a hand-to-hand combat on top these speeding machines. This could be one of the few cases where the actions of 007 could fall under the category of “political assassination” if we consider the definition given by the Cambridge Dictionary, so would the opening black and white sequence from the cinematic adaptation of Casino Royale where Daniel Craig’s pre-007 accomplishes a rudimentary assassination task of cleaning two MI6 traitors.

Nevertheless, in the 2006 it is M who clearly establishes the difference between an assassin and a 00 agent to this new recruit named James Bond in the reboot of the series directed by Martin Campbell: “Any thug can kill. Arrogance and self-awareness seldom go hand in hand”. During this tense encounter, M tells Bond off for shooting an unarmed man inside an embassy in Madagascar where he was seeking sanctuary: the African bomber Bond was supposed to interrogate, getting caught on camera and violating “the absolutely inviolable rule of international relationships” just to “kill a nobody” without extracting him any information.

As it happened in Licence To Kill, whenever Bond tries to go against the system or international laws that could compromise the image of Her Majesty’s government, he is always reminded that he isn’t a freelancer or a gun for hire without the boundaries of ethics, laws or rules, which is the exact opposite of assassins like the Jackal or Léon.

No Time to Die: Everything You Need to Know the 2nd James Bond Trailer

Daniel Craig and the Modern Bond Portrayal

In Quantum of Solace, the direct sequel of this film that opened the Daniel Craig era, the relationship between Bond and M is still tense as the secret agent continues killing “every possible lead” although in self-defence. Things reach a boiling point, once again, when 007 goes against the rules: during a fight he ends up killing a member of the Special Branch, the bodyguard of a personal envoy to the Prime Minister who was linked to a terrorist organization, the same behind the villains from the previous film. Bond refuses to report to MI6 and M immediately labels him as a threat, restricting his movements and putting an alert on all his passports. Things get even worse when Bond is suspected to having killed René Mathis, an MI6 contact, which was actually shot by two corrupt policemen in La Paz, Bolivia. And once again we get a similar Licence To Kill situation where the British and American governments consider Bond a liability and go after him as the man is trying to pursue Doming Greene, the only lead he could link to this terrorist organization known as Quantum.

Despite describing James Bond as an “assassin” even in one of the script drafts, the most recent 007 adventure SPECTRE also deals with this angle of Bond’s personality as he opts not to kill his arch-nemesis Ernst Stavro Blofeld (rebooted as a foster brother to the secret agent, and played by Christoph Waltz) and has him arrested under terrorism charges.

However, the film begins during a “Day of The Dead” parade in Mexico City where Bond takes an assassination job, but this task is actually a posthumous request by the deceased M played by Judi Dench: “If anything happens to me, 007, I want you to find a man called Marco Sciarra. Kill him… and don’t miss the funeral”, the recorded message left in Bond’s mailbox says. When the British agent is about to pull the trigger while pointing to Sciarra’s head from the building across, we heard a dialogue in Italian where the man talks about blowing up a stadium full of people – reinforcing this idea that Bond “only kills professionals” and won’t do this job for the highest bidder or without some ethic code behind.

In the end, the “assassination” mission turns into an operation to prevent a terrorist attack and the death of Sciarra takes place after a long chase on foot and a fight inside a helicopter flying over the Zócalo Square. Yet again, Ralph Fiennes’ character Gareth Mallory, who has taken over the position of M at the British Intelligence, grounds Bond and relieves him from active duty for doing this job (which caused the destruction of two buildings in Mexico) “without authority”.

It is important to note that this new leader of MI6 will still defend the activities of the 00 section against the “Whitehall mandarin” played by Andrew Scott in the second Bond film directed by Sam Mendes: “Have you ever had to kill a man, Max? Have you? To pull that trigger, you have to be sure. Yes, you can analyse, investigate, assess, target, but then you have to look him in the eye, and you make the call. (…) A licence to kill is also a licence not to kill.” With these words, M marks the difference between Bond or any member of the 00 section and thugs or contract killers.

Upon making this analysis, the most obvious conclusion is that considering James Bond an “assassin” is strictly tied to a simplistic interpretation of the word “assassin”, where simply the fact of a person taking the life of another person makes him one. However, when counterbalancing all the assessment, judgment, investigation and even hunches Bond had before pulling a trigger – and the presence of certain “rules” that respond to ethics that are somewhat similar to those of a law enforcement agency, we could definitely say that James Bond is not an assassin – not at least in the way we often make it to be when comparing him to other Hollywood characters.